Gut-Liver Connection Symptom Checker

Check Your Symptoms

Select symptoms that apply to your situation. This tool helps identify potential overlap between atrophic gastroenteritis and autoimmune hepatitis.

Analysis Results

Risk Assessment:

Recommended Actions:

Explanation:

When you hear the terms Atrophic Gastroenteritis is a chronic inflammation that leads to thinning of the intestinal lining, often causing malabsorption and Autoimmune Hepatitis is a condition where the immune system attacks liver cells, leading to inflammation and possible cirrhosis, you might wonder if they are completely unrelated or if they share a hidden connection. The short answer: they often overlap because the gut and liver talk to each other through the bloodstream, and a mis‑directed immune system can affect both organs at once.

Key Takeaways

- Both diseases are driven by an immune response that mistakes body tissue for a threat.

- The gut‑liver axis allows inflammatory signals from an inflamed intestine to reach the liver.

- Patients with atrophic gastroenteritis frequently show liver‑enzyme abnormalities that may signal autoimmune hepatitis.

- Diagnosis relies on blood tests, imaging, and tissue biopsies of both the intestine and liver.

- Treatment usually combines nutritional support for the gut with immunosuppressive drugs for the liver.

What Is Atrophic Gastroenteritis?

Atrophic gastroenteritis describes a long‑term inflammation that causes the lining of the small intestine, especially the duodenum and jejunum, to become thinner (atrophic). This thinning reduces the surface area for nutrient absorption, leading to symptoms like chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and vitamin deficiencies.

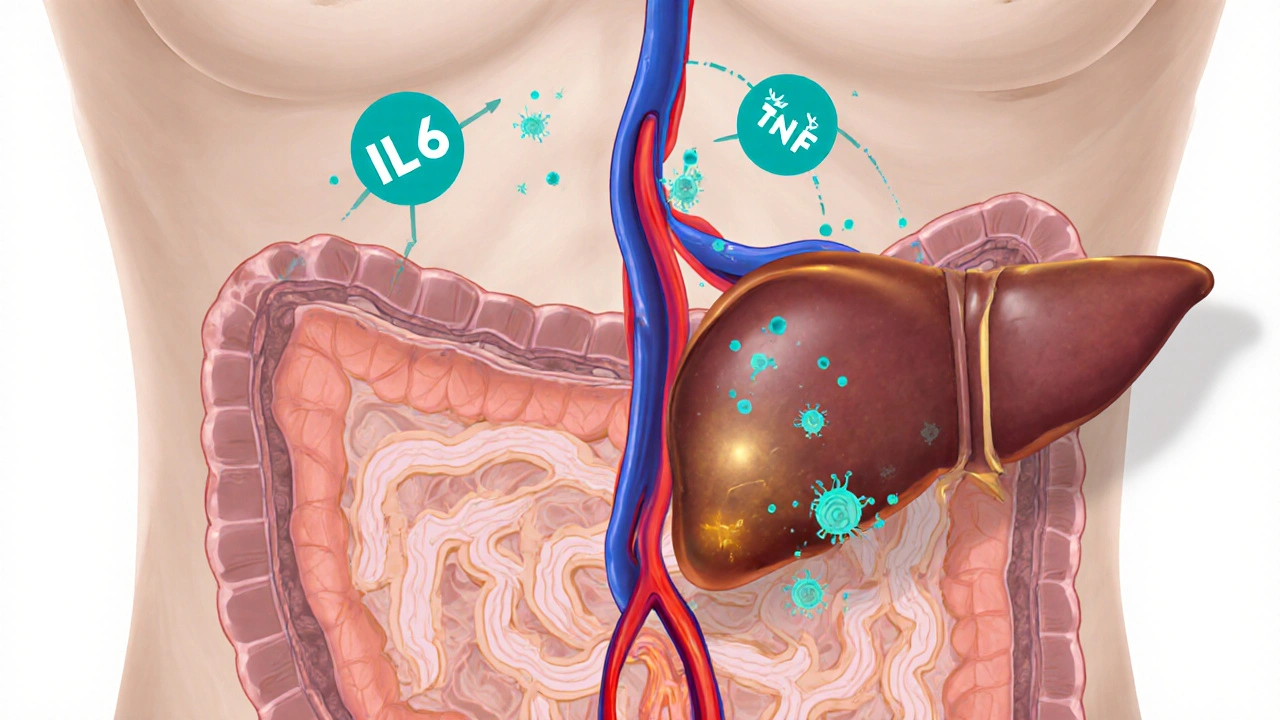

The condition is often linked to celiac disease, tropical sprue, or autoimmune processes that target the intestinal mucosa. When the immune system releases Inflammatory Cytokines such as interleukin‑6 (IL‑6) and tumor necrosis factor‑alpha (TNF‑α), the damage spreads beyond the gut, setting the stage for extra‑intestinal manifestations.

What Is Autoimmune Hepatitis?

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic liver disease in which the body’s immune defenses mistakenly attack hepatocytes. People with AIH typically have elevated aminotransferases (ALT, AST), high IgG levels, and specific auto‑antibodies like anti‑smooth muscle (SMA) or anti‑liver‑kidney microsomal (LKM) antibodies.

Genetic predisposition plays a role; certain HLA genes (especially HLA‑DR3 and HLA‑DR4) increase the risk. The disease can progress to fibrosis and cirrhosis if left untreated, but most patients respond well to immunosuppressive therapy.

How the Gut and Liver Talk: The Gut‑Liver Axis

The liver receives about 70% of its blood supply from the portal vein, which drains the gastrointestinal tract. This direct link means that anything that happens in the gut-microbial changes, barrier breakdown, or inflammation-can quickly reach the liver.

When atrophic gastroenteritis damages the intestinal barrier, bacterial products like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) slip into the portal circulation. LPS triggers Immune System activation in the liver, promoting cytokine release and possibly igniting an autoimmune attack on liver cells.

Studies published in the last three years (e.g., a 2023 multicenter cohort) showed that 22% of patients with severe atrophic changes also had elevated liver enzymes consistent with AIH, supporting a real biological connection rather than coincidence.

Clinical Overlap: When Symptoms Blur the Lines

Both conditions can cause fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal discomfort. However, certain clues help differentiate or confirm overlapping disease:

- Blood tests: Low ferritin or vitamin B12 points to gut malabsorption, while high IgG and positive auto‑antibodies suggest AIH.

- Imaging: Ultrasound may reveal a homogenous liver in early AIH, whereas CT or MRI can show bowel wall thinning in atrophic gastroenteritis.

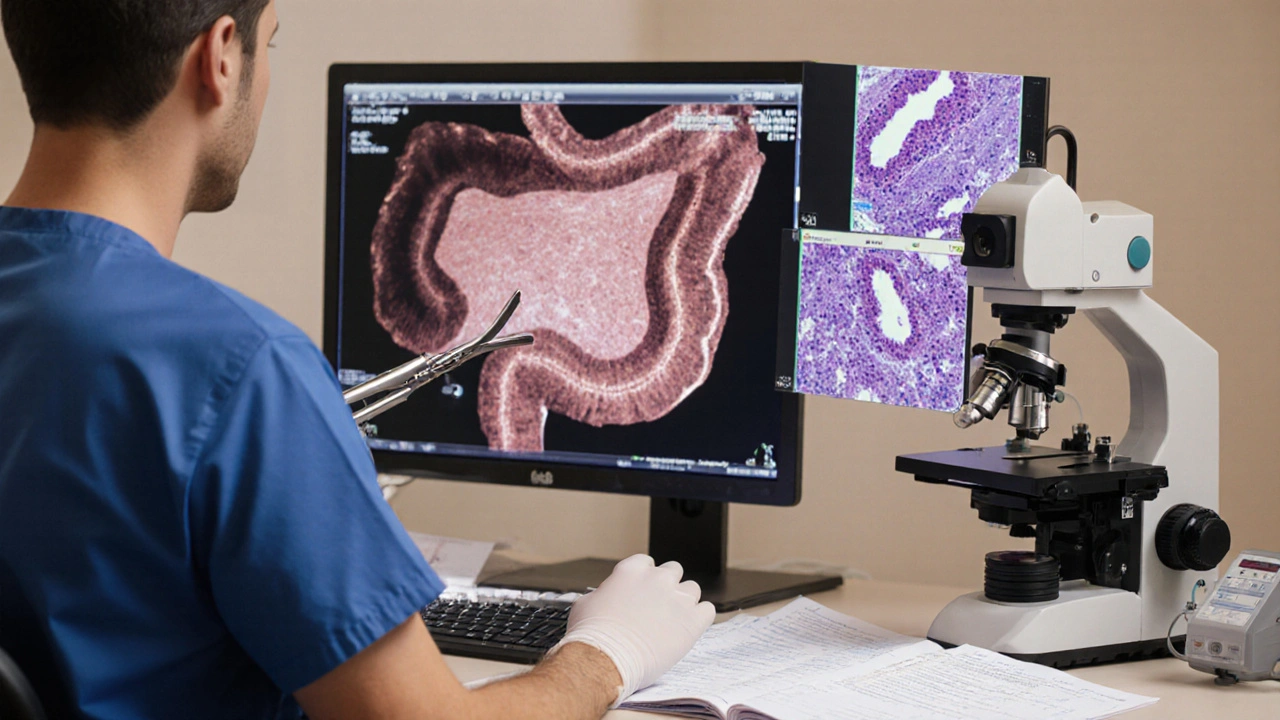

- Biopsy: A duodenal biopsy showing villous atrophy confirms intestinal involvement; a liver biopsy revealing interface hepatitis (lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate) confirms AIH.

Because the two diseases often coexist, clinicians recommend a combined diagnostic work‑up when a patient presents with unexplained liver‑enzyme spikes and chronic diarrhea.

Diagnosis: Putting the Pieces Together

- Screen blood work: AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, IgG, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), SMA, LKM.

- Order stool studies: rule out infection, check for fat malabsorption.

- Perform upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies to assess villous height and intra‑epithelial lymphocytes.

- Schedule a liver biopsy if auto‑antibodies are positive and liver enzymes remain high despite ruling out viral hepatitis.

- Consider HLA typing to identify genetic susceptibility.

Combining these steps yields a robust picture of whether the gut, the liver, or both are under immune attack.

Treatment Strategies: Tackling Both Fronts

Because the diseases share an immune‑driven basis, therapy often overlaps.

1. Nutritional Rehabilitation for Atrophic Gastroenteritis

- High‑calorie, gluten‑free (if celiac) or lactose‑restricted diet.

- Supplement vitamins and minerals: iron, folate, B12, fat‑soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K).

- Probiotics may help restore a healthier gut microbiome, reducing LPS leakage.

2. Immunosuppression for Autoimmune Hepatitis

First‑line therapy typically starts with Corticosteroids (prednisone) at 30‑60mg daily, followed by a taper as liver enzymes normalize. Most patients need a steroid‑sparing agent to limit side effects:

- Azathioprine (1-2mg/kg/day)

- Alternative: Mycophenolate Mofetil (1-1.5g/day)

In refractory cases, biologics targeting specific cytokines (e.g., anti‑TNF agents) have shown promise, though data are still emerging.

3. Monitoring and Adjustments

Regular follow‑up every 3months during the first year includes liver‑function panels, complete blood counts, and assessment of nutritional status. Repeat endoscopy or liver imaging is reserved for persistent abnormalities.

Practical Checklist for Patients and Clinicians

| Step | What to Do | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Order baseline labs (AST, ALT, IgG, auto‑antibodies) | Detect liver involvement early |

| 2 | Schedule upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies | Confirm villous atrophy and rule out other causes |

| 3 | Consider HLA‑DR typing if family history exists | Identify genetic predisposition |

| 4 | Start nutritional supplements tailored to deficiencies | Improves gut healing and overall energy |

| 5 | Begin immunosuppressive regimen (prednisone ± azathioprine) | Reduces liver inflammation and prevents fibrosis |

| 6 | Monitor labs every 8‑12 weeks initially | Adjust medication dose before side‑effects appear |

| 7 | Re‑evaluate with repeat endoscopy or liver biopsy if no improvement | Ensures that the correct disease is being treated |

Future Directions: Research on the Gut‑Liver Immune Bridge

Scientists are digging deeper into how intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”) fuels liver autoimmunity. Ongoing trials (2024‑2025) are testing oralbudesonide formulations that target gut inflammation without systemic steroid exposure, hoping to lower the risk of AIH flare‑ups.

Another promising avenue is gut‑focused microbiome transplantation. Early‑phase data suggest that restoring a balanced microbiota can dampen systemic cytokine storms, potentially lowering the need for high‑dose immunosuppression.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can atrophic gastroenteritis cause liver damage on its own?

Yes. When the intestinal barrier is compromised, bacterial toxins travel to the liver via the portal vein, triggering inflammation that can evolve into autoimmune hepatitis if the immune system overreacts.

Do I need a liver biopsy if I already have a duodenal biopsy confirming atrophy?

A liver biopsy isn’t mandatory for everyone, but it’s recommended when liver enzymes stay high despite treating the gut or when auto‑antibodies are present. The biopsy confirms interface hepatitis, which guides therapy.

Are there lifestyle changes that help both conditions?

A balanced, nutrient‑dense diet, regular moderate exercise, and avoidance of alcohol are core. Reducing stress can also lower cortisol, which otherwise fuels inflammation.

How long does immunosuppressive therapy usually last?

Most patients stay on a low‑dose maintenance (often azathioprine alone) for several years, sometimes indefinitely, to keep the liver in remission.

Is there a risk of cancer when both diseases are present?

Chronic inflammation does raise the long‑term risk of liver cancer, especially if cirrhosis develops. Routine surveillance ultrasound every 6‑12 months is advised for high‑risk patients.

Rica J

October 6, 2025 AT 17:21Wow, this gut-liver link is pretty wild. Atrophic gastroenteritis and autoimmune hepatitis sound like a nasty combo, but the body’s immune system can be a real over‑reactor. If you’re dealing with chronic diarrhea or unexplained weight loss, it could be more than just a bad diet. Also keep an eye on those liver enzymes – they can sneak up on you. Bottom line, if you suspect any of these symptoms, seeing a gastro‑enterologist and a hepatologist is a smart move.

Linda Stephenson

October 6, 2025 AT 19:01It's fascinating how the gut and liver communicate, especially when the immune system gets confused. People often overlook vitamin deficiencies, which can aggravate both conditions. A balanced diet rich in B12 and iron can help keep things steady while you sort out the medical side. Remember, staying proactive with regular check‑ups can make a huge difference.

Sunthar Sinnathamby

October 6, 2025 AT 20:41Listen up – if you’ve got chronic diarrhoea and your liver tests are off, don’t wait around. The immune system can go rogue fast, and you’ll want to shut it down before it wrecks more of your body. Get a proper work‑up ASAP and start those immunosuppressants if the docs say so. No one wants to be stuck in a cycle of fatigue and joint pain.

Catherine Mihaljevic

October 6, 2025 AT 22:21Sounds like a fancy way to scare patients into buying supplements.

Michael AM

October 7, 2025 AT 00:01Hey folks, just a heads‑up – if you notice persistent fatigue along with liver enzyme spikes, it could be more than just stress. Talk to your doctor about getting a full autoimmune panel; early detection can really improve outcomes. Also, keep track of any joint pain, as that’s a common red flag. Stay on top of it and don’t ignore the little stuff.

Rakesh Manchanda

October 7, 2025 AT 01:41While the lay‑person may find these medical terms daunting, a nuanced understanding of the gut‑liver axis is indispensable for the discerning patient. One must scrutinise the interplay of cytokine cascades and antigenic exposure, lest the clinician overlook a subclinical presentation. Consider integrating a comprehensive metabolic panel alongside serologic assays for auto‑antibodies. Such a rigorously curated approach ensures therapeutic precision.

Erwin-Johannes Huber

October 7, 2025 AT 03:21Just wanted to add that staying hydrated and getting enough rest can actually support your immune system while you’re dealing with these issues. It’s easy to forget the basics when you’re focused on labs and meds.

Tim Moore

October 7, 2025 AT 05:01Esteemed colleagues, the interrelationship between atrophic gastroenteritis and autoimmune hepatitis warrants a methodical exploration of both histopathological findings and serological markers. It would be prudent to convene a multidisciplinary panel to delineate diagnostic criteria and therapeutic algorithms. Such scholarly discourse will undoubtedly augment our collective clinical acumen.

Erica Ardali

October 7, 2025 AT 06:41The drama of a gut‑liver love story is overhyped, but sure, it makes a good blog post. If you’re into that sort of thing, read the paper, otherwise, just get your meds.

Justyne Walsh

October 7, 2025 AT 08:21Oh, great, another excuse for the NHS to spend money on fancy tests while the real issue is people eating bad food. If you want health, stop buying processed snacks, not the other way around.

Callum Smyth

October 7, 2025 AT 10:01Hey team, just a reminder to keep an eye on vitamin B12 levels – deficiency can make both gut and liver symptoms worse. 😊 Also, regular follow‑ups can catch flare‑ups early.

Xing yu Tao

October 7, 2025 AT 11:41It is a matter of epistemological significance that the physiological crosstalk between the intestine and hepatic system be subject to rigorous ontological scrutiny. One must consider the phenomenology of symptom manifestation alongside the biochemical pathways. In doing so, we may arrive at a more holistic paradigm of patient care.

Adam Stewart

October 7, 2025 AT 13:21Just wanted to mention that I’ve been tracking my symptoms in a journal, and it’s helped me notice patterns I’d otherwise miss.

Selena Justin

October 7, 2025 AT 15:01Good point on early detection. In my experience, a collaborative approach between gastroenterology and hepatology yields the best patient outcomes, especially when autoimmune markers are borderline.

Bernard Lingcod

October 7, 2025 AT 16:41I’m curious about how much diet actually influences the autoimmune component. Could eliminating certain triggers reduce the need for immunosuppressants? It’d be great to see more research on that.

Raghav Suri

October 7, 2025 AT 18:21Honestly, the whole thing feels like a wild rollercoaster. One day you’re fine, the next your liver’s acting up. Staying chill helps, but you gotta be aggressive about getting tests done.

Freddy Torres

October 7, 2025 AT 20:01All right, this gut‑liver saga is splendiferous – if you can keep the symptoms in check, you’ll feel like a rockstar.

Andrew McKinnon

October 7, 2025 AT 21:41From a pathophysiological standpoint, the cytokine-mediated inflammation bridges the mucosal immunity and hepatic stellate activation – basically, the body’s own sabotage protocol.

Dean Gill

October 7, 2025 AT 23:21Let me break this down for anyone still trying to piece together why atrophic gastroenteritis and autoimmune hepatitis keep showing up together. First, think about the gut as a massive immune organ – it’s loaded with lymphoid tissue and constantly exposed to antigens from food and microbes. When atrophy hits the intestinal lining, you lose not only absorptive surface but also a key regulatory barrier that keeps those antigens in check. That loss can lead to increased permeability, often called "leaky gut," which lets bacterial fragments and toxins slip into the bloodstream. Once those molecules reach the liver via the portal vein, the hepatic immune cells, especially Kupffer cells, recognize them as foreign and launch an inflammatory response. That’s the first link: gut barrier dysfunction feeds the liver with inflammatory triggers. Second, both conditions share a common thread of dysregulated immune tolerance. In atrophic gastroenteritis, you often see auto‑antibodies targeting intestinal epithelial cells; in autoimmune hepatitis, you have auto‑antibodies against liver antigens like smooth‑muscle or liver‑kidney microsomal proteins. The underlying genetic predisposition, often HLA‑DR alleles, can predispose someone to both kinds of auto‑immunity. Third, vitamin deficiencies, especially B12 and iron, exacerbate the situation because they’re essential for DNA synthesis and immune regulation; deficits can worsen both gut mucosal health and hepatic repair mechanisms. Fourth, chronic fatigue and joint pain are systemic symptoms that arise from the same cytokine milieu – think TNF‑α, IL‑6, and interferon‑γ – circulating throughout the body. Finally, the treatment overlap is notable: immunosuppressants like azathioprine or corticosteroids can target both the gut inflammation and hepatic autoimmunity, while dietary modifications, probiotics, and careful monitoring of liver enzymes provide supportive care. So, when you see these two diseases together, it’s rarely a coincidence – there’s a mechanistic cascade linking gut barrier breakdown, immune cross‑reactivity, and shared genetic factors. Keeping an eye on liver function tests when dealing with chronic gastroenteritis, and vice versa, is just good clinical sense.

Royberto Spencer

October 8, 2025 AT 01:01One could argue that the real lesson here is the philosophical absurdity of compartmentalizing the human body into isolated systems. When the gut whispers, the liver shouts – it’s a reminder of our interconnectedness.