When you pick up a prescription, you might not realize that the drug you’re getting isn’t always the one your doctor originally wrote. In many states, pharmacists are allowed to swap out brand-name drugs for generics without asking you first. This isn’t random-it’s the result of deliberate state policies designed to save money on prescription drugs. And it’s working. Across the U.S., states have built a patchwork of rules, financial nudges, and legal requirements to push doctors, pharmacists, and patients toward cheaper generic medications. The goal? Lower costs without lowering care.

How States Save Money Without Sacrificing Care

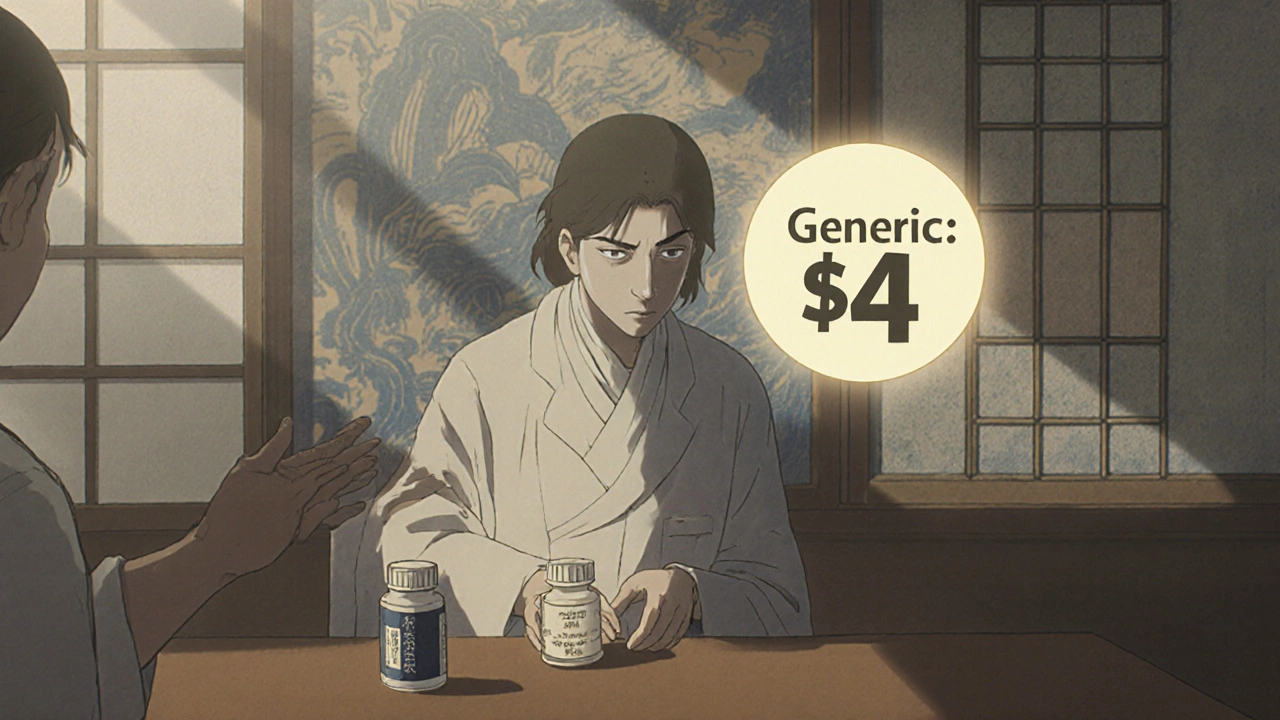

Generic drugs aren’t cheaper because they’re worse. They’re cheaper because they don’t need expensive clinical trials. Once a brand-name drug’s patent expires, other companies can make the same medicine using the same active ingredients. The FDA requires generics to be just as safe and effective. So why do brand-name drugs still dominate prescriptions? Price. A 30-day supply of a brand-name blood pressure pill might cost $120. The generic? $4.

States stepped in because Medicaid and other public health programs were spending billions on brand-name drugs that had generic alternatives. In 2019, 46 out of 50 states had a Preferred Drug List (PDL) for Medicaid prescriptions. These lists tell doctors and pharmacists which drugs are the most cost-effective. If a doctor prescribes a drug not on the list, the pharmacy might refuse to fill it-or the patient pays more out of pocket.

It’s not just about blocking brand drugs. States also reward pharmacies and patients for choosing generics. Some states pay pharmacists a higher fee to dispense a generic. Others require patients to pay a $10 copay for a brand drug but only $5 for the generic. That small difference changes behavior. People are more likely to pick up their meds if they cost less. And pharmacies? They’re incentivized to swap out the expensive version-even if the doctor didn’t ask for it.

The Power of Presumed Consent

One of the most effective tools states use is called presumed consent. This means pharmacists can automatically substitute a generic drug unless the doctor writes “dispense as written” or the patient says no. It’s the opposite of explicit consent, where the patient must give permission before the swap happens.

A 2018 study from the National Institutes of Health found that states with presumed consent laws saw a 3.2 percentage point increase in generic dispensing compared to states that required patient permission. That might sound small, but multiply that across millions of prescriptions, and you’re talking about billions in savings. The study estimated that if all 39 states with explicit consent laws switched to presumed consent, they could save $51 billion a year.

Why does this work so well? Because it removes friction. Most patients don’t care if they get the generic. They just want the medicine to work. But if you have to ask them every time, they might forget, get confused, or say no out of habit. Presumed consent makes the smart choice the easy choice.

Why Mandatory Substitution Doesn’t Work

Some states tried forcing pharmacists to substitute generics no matter what. But research shows those rules barely moved the needle. Why? Pharmacists were already substituting generics anyway-they made more money on them. The profit margin on a generic drug can be 10 times higher than on a brand-name one. So even without a law, pharmacists had a strong reason to swap.

What really changes behavior isn’t forcing the pharmacist. It’s changing what the patient pays. When a patient sees a $20 copay for a brand drug and a $5 copay for the generic, they choose the cheaper option. That’s why states are moving away from top-down mandates and toward patient-facing incentives. The real leverage isn’t in the pharmacy counter-it’s in the wallet.

Medicaid’s Hidden Engine: The Rebate System

Behind every generic drug on a state’s Preferred Drug List is a complex financial deal called the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. Since 1990, federal law has required drugmakers to pay rebates to states for every prescription filled through Medicaid. For generics, the minimum rebate is 13% of the drug’s average price. But states don’t stop there. Forty-six states in 2019 negotiated extra rebates on top of that-sometimes doubling or tripling the savings.

These rebates are why states can afford to make generics the default. The more generics they use, the more money they get back from drug companies. It’s a self-reinforcing loop: lower prices → higher use → bigger rebates → more savings. That’s why states like California and New York have some of the most aggressive generic substitution policies-they’re not just trying to cut costs, they’re building a financial system that rewards cheaper drugs.

But there’s a catch. Sometimes, generic manufacturers face unexpected rebate increases that make their drugs unprofitable. If a generic drug’s price stays the same but Medicaid’s rebate formula changes, the manufacturer might lose money on every pill sold. That’s led to shortages in some cases, where a generic disappears from shelves because no one wants to make it anymore. States are learning this the hard way-pushing too hard on price can break the supply chain.

340B and the Safety-Net Puzzle

Another layer of the puzzle is the 340B Drug Pricing Program. Created in 1992, it lets hospitals and clinics that serve low-income patients buy drugs at steep discounts-often 20% to 50% off. These are safety-net providers: community health centers, rural hospitals, free clinics. They rely on 340B to stretch their budgets.

But here’s the twist: states have to reimburse these providers for Medicaid prescriptions based on what they actually paid (called Actual Acquisition Cost), not a fixed rate. After a 2016 federal rule, states had to align their payments with 340B prices. That meant some states had to pay pharmacies less for brand-name drugs, which pushed providers even harder toward generics. It wasn’t a policy change-it was a financial domino effect.

For patients at these clinics, it means more access to affordable meds. For states, it means tighter control over how drug money flows. But it also creates tension. If a pharmacy’s reimbursement drops too low, they might stop carrying certain generics. Or worse-they might stop serving 340B patients altogether.

What’s Next? The Drug List

At the federal level, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is testing a new idea: the $2 Drug List. It’s simple-any generic drug that costs $2 or less per 30-day supply gets a flat copay of $2, no matter what. No prior authorization. No complex formularies. Just an easy, predictable price.

This isn’t mandatory for states, but it’s a blueprint. If it works for Medicare Part D beneficiaries, states might copy it for Medicaid. The idea is to cut through the noise. Patients don’t need to understand formularies or rebates. They just need to know: “This pill is $2. That one’s $40. Pick the $2 one.”

It’s a shift from complex regulation to simple clarity. And it might be the future. States are realizing that the best way to get people to choose generics isn’t to punish them for choosing brands-it’s to make the generic option so easy and affordable that it’s the only choice that makes sense.

The Big Picture: Savings, Risks, and Real People

States have saved hundreds of billions by pushing generics. But it’s not all smooth sailing. Drug shortages, rebate surprises, and manufacturer pullouts are real risks. And while most patients don’t mind generics, some worry they’re “second-rate.” That’s where education matters. A patient who understands that the generic for their asthma inhaler is identical in effectiveness is more likely to stick with it.

The real success of these policies isn’t in the numbers-it’s in access. A diabetic in rural Ohio can afford insulin because the state made the generic version the default. A veteran in Michigan gets his blood pressure pills without skipping doses because his copay is $5, not $50. That’s what these laws are really about: making sure people get the medicine they need, without going broke.

There’s no perfect system. But the trend is clear: the future of drug pricing isn’t about controlling doctors. It’s about designing systems where the cheapest, safest option is also the easiest one to choose.

Are generic drugs really as good as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also meet the same strict standards for quality, purity, and effectiveness. The only differences are in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes) and packaging. For over 90% of prescriptions, generics work just as well-and cost a fraction of the price.

Can my pharmacist switch my brand-name drug without telling me?

In 31 states with presumed consent laws, yes-pharmacists can substitute a generic without asking you, unless the doctor specifically wrote "dispense as written" on the prescription. In the other 19 states, pharmacists must get your permission first. Always check your receipt or ask the pharmacist if you’re unsure what you received.

Why do some generic drugs cost more than others?

Even among generics, prices vary. That’s because multiple companies can make the same drug, and competition drives prices down. But if only one company makes a generic, or if there’s a shortage, the price can spike. Some states use Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists to cap how much they’ll pay for a generic, which helps keep prices stable.

Do generic prescribing laws hurt drug innovation?

No. Generic laws target drugs whose patents have already expired. They don’t affect new drugs still under patent protection. In fact, by lowering overall drug spending, they free up money for other healthcare needs. The real pressure on innovation comes from high prices on new brand-name drugs-not from the use of older generics.

What happens if a generic drug I rely on disappears?

If a generic is pulled from the market due to shortages or unprofitability, your pharmacy will notify you and your doctor. You may need to switch to another generic version or, in rare cases, go back to the brand-name drug. Some states track drug availability closely and work with manufacturers to prevent shortages. If you’re concerned, ask your pharmacist to alert you if your medication changes.

Robert Merril

November 17, 2025 AT 12:14So let me get this right the government pays pharmacists extra to give me a pill that works the same but costs 10x less and somehow this is controversial

People are gonna freak out because they think generics are made in a basement by dudes named Boris but the FDA says its the same damn thing

Also why are we still paying 120 for blood pressure meds when the generic is 4 i dont even know anymore

Georgia Green

November 19, 2025 AT 03:01Just a heads up i had a generic for my thyroid med last year and it made me feel awful turns out the filler was different and my body reacted

Not saying all generics are bad but dont assume theyre all identical

Ask your pharmacist for the manufacturer code if you notice a change in how you feel

Julie Roe

November 20, 2025 AT 02:17I love how this post breaks down the real mechanics behind drug pricing instead of just screaming about corporate greed

Most people dont realize that the real leverage isnt in forcing pharmacists to swap drugs its in making the patient feel like theyre getting a better deal

That $5 vs $20 copay difference is a psychological game changer

And the Medicaid rebate system is genius really its like a tax incentive for doing the right thing

Its not about controlling doctors its about making the smart choice the easy choice

And honestly if you can save billions without compromising care why wouldnt you do it

People worry about shortages but thats usually because the price is too low for manufacturers to make money not because the system is broken

We need more of these smart nudges not more mandates

Also the $2 drug list idea is brilliant simple clean and patient centered

Imagine if every prescription was like this no confusing formularies no prior auth just pick the one that costs two bucks

Thats healthcare we can actually understand

Roberta Colombin

November 20, 2025 AT 10:39As someone who works with rural clinics i can tell you the 340B program is a lifeline

Without it many of our patients would choose between food and medicine

But when states cut reimbursement too low pharmacies start dropping out

Its not about profit its about survival

We need policies that support access not just cost savings

Generics are great but only if theyre available

And if a patient cant get their medication because the pharmacy stopped stocking it because the reimbursement is too low then weve lost the point

Christina Abellar

November 21, 2025 AT 20:22My pharmacist swapped my generic without telling me and i didnt even notice

Works fine

Jennifer Howard

November 22, 2025 AT 13:58While the premise of this article is superficially compelling it fundamentally misrepresents the ethical and legal implications of presumed consent in pharmaceutical substitution

One cannot ethically assume consent for a medical intervention even when the clinical outcome is statistically equivalent

The FDA equivalence standard is a legal fiction designed to facilitate corporate profit under the guise of public health

Patients have a fundamental right to autonomy over their pharmacological regimen and the substitution of a branded medication with a generic constitutes a material change in treatment protocol regardless of bioequivalence

Furthermore the rebate system creates perverse incentives that distort the market and ultimately reduce innovation in the long term

The notion that patients do not care is patronizing and reflects a profound misunderstanding of medical agency

One must not confuse cost efficiency with ethical governance

The slippery slope of presumed consent leads inevitably to paternalistic healthcare systems where individual rights are subordinated to fiscal targets

This is not progress it is the commodification of human health

Dave Feland

November 22, 2025 AT 19:50Did you know that the FDA allows generics to vary by up to 20 in bioavailability

That means your generic blood pressure pill could be 20 weaker or stronger than the brand

And the rebate system is just a front for Big Pharma to control the market through monopolies on inactive ingredients

They make the generic cheaper to produce but add a weird filler that causes long term kidney damage

And the $2 drug list

That’s just the first step before they start putting tracking chips in the pills

Next thing you know your insulin is being monitored by the CDC

And they’ll tell you when to take it

They’ve been doing this since the 1970s

They want you dependent on the system

They dont want you healthy they want you compliant

Ashley Unknown

November 22, 2025 AT 22:43Okay so let me get this straight

Theyre swapping my meds without telling me

And then theyre paying pharmacists to do it

And the government is getting rebates from drug companies

And now theyre thinking about a $2 drug list

But wait

What if the generic is made in China

What if the active ingredient is the same but the filler is laced with something

What if the pharmacist is just a pawn in a bigger scheme

What if the whole thing is a cover for pharmaceutical corporations to dump old stock

What if my thyroid meds are actually causing my anxiety

What if the FDA is in on it

What if this is how they control the population

And what if the $2 drug list is just the beginning

And what if next they make all prescriptions mandatory

And what if they start printing the pills with barcodes that link to your social security number

And what if they track your compliance

And what if they cut your benefits if you dont take the generic

And what if this is all part of the New World Order

And what if my pharmacist knows but wont tell me

And what if I’m the only one who sees it

And what if I’m not crazy

And what if I’m the only one who cares

Jennie Zhu

November 24, 2025 AT 09:24The structural economics underpinning state-level generic substitution policies are predicated upon a confluence of regulatory arbitrage and fiscal externalization

The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program functions as a de facto price ceiling mechanism wherein manufacturers are compelled to subsidize public expenditures through mandatory rebate structures

When coupled with Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) formularies and presumed consent statutes, these mechanisms create a non-linear incentive architecture wherein pharmacy reimbursement dynamics override prescriber autonomy

Notably, the 340B program introduces a parallel layer of price suppression that further distorts market equilibrium for safety-net providers

While the empirical outcomes demonstrate significant cost containment, the unintended consequences include therapeutic substitution-induced adverse events, supply chain fragility due to margin compression, and erosion of patient trust through procedural opacity

Moreover, the absence of robust pharmacovigilance protocols for generic-specific adverse reactions constitutes a latent public health vulnerability

Policy design must therefore evolve beyond cost-efficiency metrics to incorporate patient-reported outcomes, manufacturer accountability, and dynamic formulary monitoring

The $2 Drug List, while administratively elegant, risks exacerbating the very supply chain vulnerabilities it seeks to mitigate through homogenization of pricing incentives

True innovation lies not in simplification but in calibrated, evidence-based governance

Kathy Grant

November 26, 2025 AT 06:32I read this and I felt this deep quiet relief

Not because I’m some policy wonk but because I’ve seen what happens when people can’t afford their meds

I watched my neighbor skip her insulin doses because the brand was $400 and she was working two jobs

She didn’t know the generic was the same

She just knew she couldn’t pay

And then one day she got a call from the clinic saying they could switch her

She cried

Not because she was happy about the generic

But because she could breathe again

That’s what this is about

Not rebates or formularies or even the FDA

It’s about someone getting to live

Yes there are risks

Yes sometimes generics disappear

But the alternative is worse

People dying because they can’t afford to live

So yeah let’s fix the shortages

Let’s make sure manufacturers aren’t losing money

But let’s not throw out the system because it’s not perfect

It’s saving lives

And that’s worth fighting for

Noel Molina Mattinez

November 27, 2025 AT 07:13Pharmacists are swapping meds without telling you and you dont even notice

That’s the point

Theyre not supposed to tell you

Theyre supposed to make the swap

And youre supposed to be grateful

And if you complain theyll say you dont understand the system

But you know what

Theyre not swapping your meds

Theyre swapping your rights

And no one is talking about it

Not even the doctors

Theyre all in on it

And you just keep taking your pills

And never asking why

And that’s the real problem