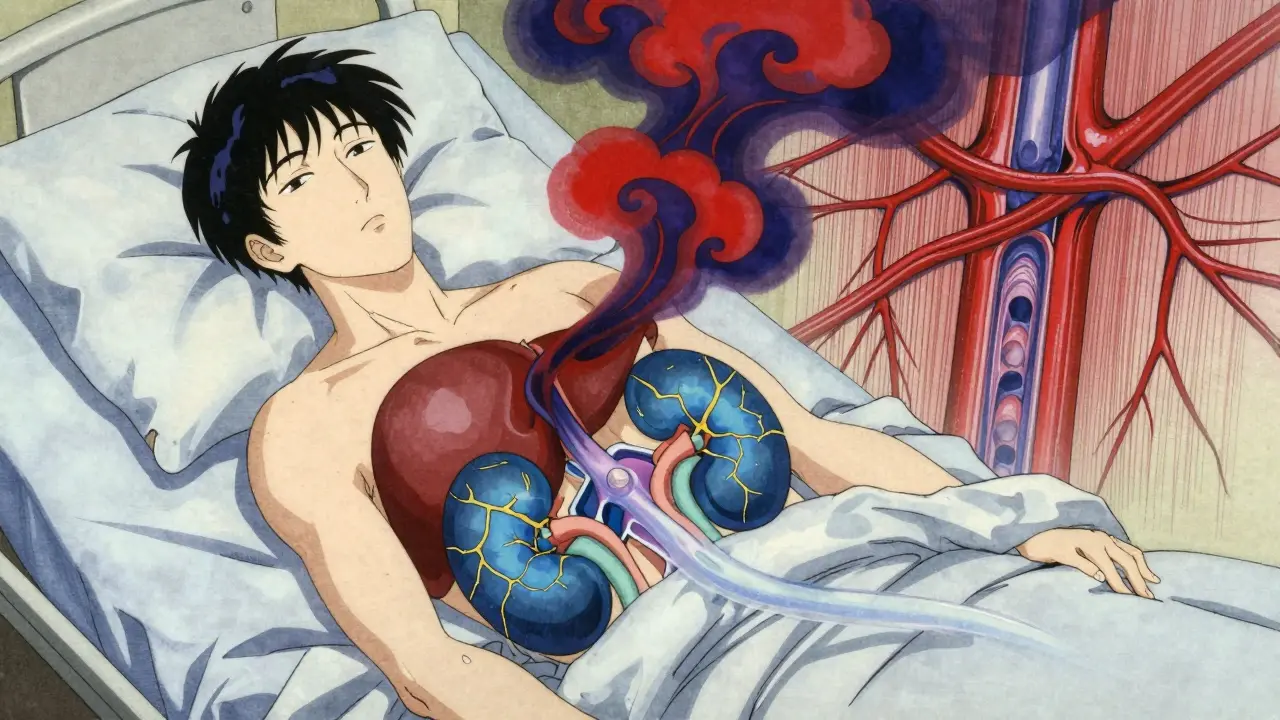

When your liver fails, your kidneys don’t just slow down-they can shut down completely. This isn’t a coincidence. It’s hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), a deadly chain reaction where advanced liver disease triggers sudden, severe kidney failure without any physical damage to the kidneys themselves. It’s not a standalone disease. It’s a warning sign that your body’s circulation has collapsed, and your kidneys are paying the price.

What Exactly Is Hepatorenal Syndrome?

Hepatorenal syndrome happens almost exclusively in people with cirrhosis or end-stage liver disease. It’s not like a kidney infection or a blocked ureter. Your kidneys look normal under a microscope. No scarring. No inflammation. No structural damage. So why do they stop working? Because your blood flow has gone haywire.

Here’s the chain: Severe liver scarring raises pressure in the portal vein (the main blood vessel feeding the liver). This forces blood to find new paths, dilating arteries in the intestines. That sounds good-until it isn’t. The body thinks it’s losing blood volume, even though there’s too much fluid overall. In response, it tightens blood vessels everywhere, especially in the kidneys. The kidneys get less blood. Less filtration. Creatinine rises. And within days, you’re in renal failure.

This isn’t theoretical. In hospitals, up to 10% of patients with advanced liver disease develop HRS. Among those with end-stage cirrhosis, it’s closer to 40%. And once it hits, survival drops fast. Without treatment, Type 1 HRS can kill you in under two weeks.

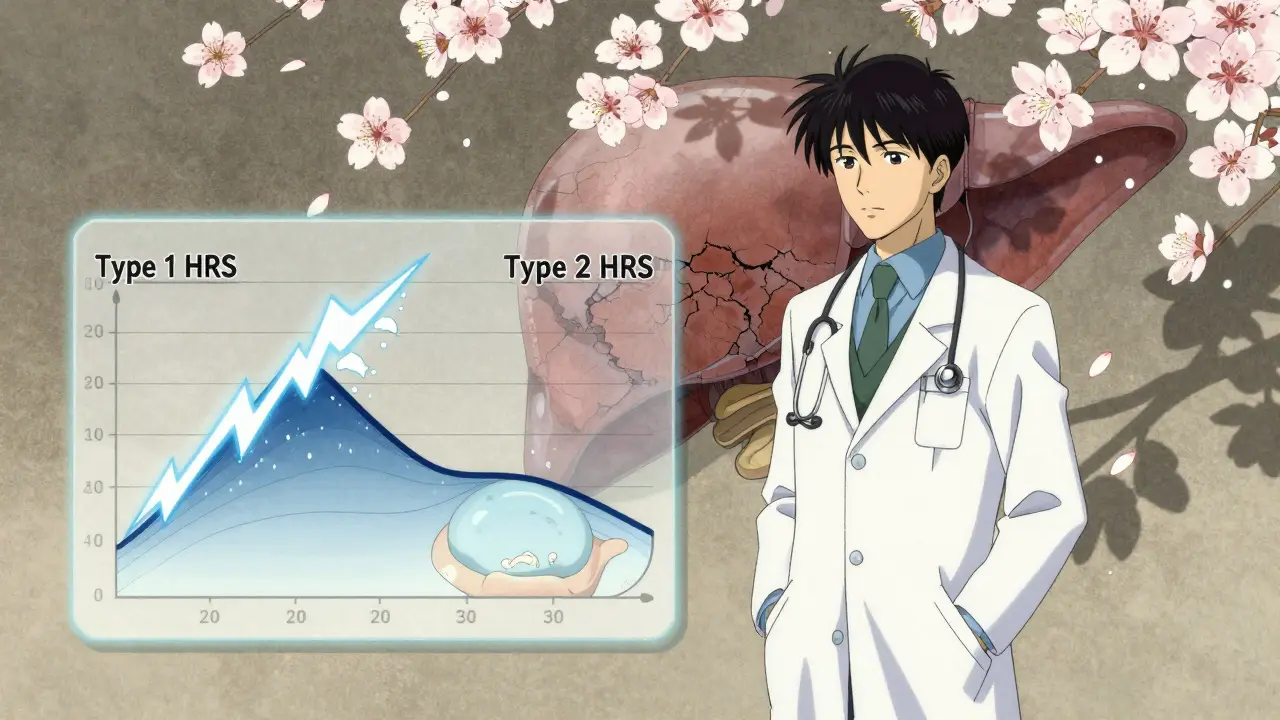

Type 1 vs. Type 2: Two Different Clocks, One Deadly Outcome

HRS isn’t one condition-it’s two. And they demand different responses.

Type 1 is the emergency. Creatinine spikes above 2.5 mg/dL in less than two weeks. It’s fast, brutal, and tied to infections, bleeding, or sudden liver decline. This is the kind that lands people in intensive care. The kidneys aren’t failing because they’re broken. They’re failing because they’re starving for blood.

Type 2 creeps in slowly. Creatinine hovers between 1.5 and 2.5 mg/dL. It’s not as immediately life-threatening, but it’s just as dangerous over time. This type almost always shows up with stubborn ascites-fluid swelling in the belly that won’t go away even with strong diuretics. Patients with Type 2 often live for months, but their quality of life collapses. They can’t sleep, eat, or move without pain.

Both types share the same root cause: circulatory chaos from liver failure. But Type 1 is a sprint. Type 2 is a slow-motion collapse.

How Doctors Diagnose It (And Why Misdiagnosis Is Common)

There’s no single test for HRS. You can’t X-ray it. You can’t biopsy it. Diagnosis is a process of elimination.

First, doctors rule out everything else: urinary tract infections, kidney stones, drug toxicity, dehydration, heart failure. Then they check urine sodium-it should be under 10 mmol/L. Plasma and urine osmolality? Urine should be more concentrated than blood. Protein in urine? Less than 500 mg/day. No blood in urine. No signs of infection.

Then comes the critical step: stop diuretics. Give 1 gram of albumin per kilogram of body weight (up to 100g) intravenously. Wait 48 hours. If creatinine doesn’t drop? That’s HRS.

Here’s the scary part: 25-30% of HRS cases get misdiagnosed. Why? Most doctors haven’t seen many. A 2021 study found only 58% of non-specialists correctly identified HRS in case scenarios. In community hospitals, protocols are rare. In academic centers, they’re standard. That gap kills people.

The Triggers No One Talks About

Most cases don’t come out of nowhere. Something sparks them.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)-an infection in belly fluid-is the #1 trigger. It happens in 35% of cases. Upper GI bleeding? That’s 22%. Acute alcoholic hepatitis? Another 11%. Even a single night of heavy drinking can push a fragile system over the edge.

These aren’t random events. They’re warning signs. If you have cirrhosis and develop fever, abdominal pain, or vomiting, don’t wait. Get checked. SBP can be treated with antibiotics-but only if caught early.

And here’s the cruel irony: many patients are on diuretics to manage ascites. But when HRS starts, those same diuretics make things worse. They dehydrate you, further cutting blood flow to the kidneys. The treatment? Stop them. Immediately.

What Actually Works: The Real Treatment Protocol

There’s no magic pill. But there is a proven path.

For Type 1 HRS: Terlipressin + albumin. Terlipressin is a vasoconstrictor. It tightens blood vessels in the intestines, redirecting blood back to the kidneys. It’s not FDA-approved in the U.S. as a standard drug-but it is now. Terlivaz™, approved in December 2022, costs about $1,100 per vial. A full 14-day course? Around $13,200. Insurance fights it. Many patients get denied. But the data is clear: 44% of patients see kidney function improve within two weeks. Without it? Survival drops to under 20% in a year.

Albumin? It’s not just a filler. It pulls fluid from tissues into the bloodstream, helping restore pressure. Give 1g/kg on day one, then 20-40g daily until kidney function improves.

For Type 2 HRS: TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt). This procedure creates a bypass inside the liver, lowering portal pressure. It works in 60-70% of cases. But it carries a 30% risk of hepatic encephalopathy-brain fog, confusion, even coma. So it’s not for everyone. Some patients get midodrine and octreotide, but those often fail.

And then there’s the only real cure: liver transplant. Without it, most patients die within months. With it? 71% survive one year. That’s why experts now say: if you have Type 1 HRS, get on the transplant list immediately. Don’t wait for creatinine to drop. Don’t wait for treatment to work. Just get listed.

The Human Cost: Pain, Delays, and Inequality

Behind every statistic is a person.

A 2023 patient survey of 312 HRS families found 78% waited over a week for a diagnosis. 63% were misdiagnosed-at least once. 41% had insurance deny terlipressin despite meeting clinical criteria.

One Reddit user shared: "My husband’s creatinine hit 3.8. We got terlipressin. It dropped to 1.9 in 10 days. But he had severe stomach pain. We had to cut the dose." Another wrote: "We tried midodrine and octreotide for six weeks. Nothing. Now we’re on the transplant list with a MELD-Na of 28. We’re praying."

And the disparities are brutal. In North America, 63% of patients get vasoconstrictors. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 11% do. Most get nothing but fluids and hope.

What’s Next? Hope on the Horizon

There’s progress. The FDA approved terlipressin for pediatric use in January 2023. MELD-Na scores now include kidney function, pushing HRS patients higher on transplant lists. New biomarkers like urinary NGAL are being tested to catch HRS before creatinine rises.

Trials are underway for new drugs. One, PB1046, targets vasopressin receptors. Another, alfapump®, automatically drains ascites fluid. If they work, they could change survival rates by 30-40% by 2027.

But until then, the rules are simple: If you have cirrhosis and your kidneys start failing, act fast. Stop diuretics. Get albumin. Demand terlipressin. Get on the transplant list. Don’t wait for a specialist to notice. Push. Advocate. Demand answers.

Hepatorenal syndrome doesn’t care about your insurance. It doesn’t care if you’re in a rural clinic. It moves fast. And if you’re not ready, it will take you.

Ken Cooper

February 8, 2026 AT 10:50Sam Dickison

February 10, 2026 AT 04:19Tom Forwood

February 10, 2026 AT 15:44John McDonald

February 10, 2026 AT 17:25Jacob den Hollander

February 12, 2026 AT 03:18Andrew Jackson

February 13, 2026 AT 22:39John Sonnenberg

February 15, 2026 AT 15:46Kathryn Lenn

February 16, 2026 AT 05:34Jonah Mann

February 17, 2026 AT 03:32THANGAVEL PARASAKTHI

February 18, 2026 AT 20:20Chelsea Deflyss

February 19, 2026 AT 13:01