Cognitive Decline Estimator

Alcohol Dependence Impact Calculator

Estimate how alcohol dependence may affect your brain function and recovery timeline based on years of use.

Cognitive Impact Summary

Affected Cognitive Domains

Executive Function

Working Memory

Long-Term Memory

Processing Speed

Recovery Timeline

With sustained abstinence:

When people think about heavy drinking, they often picture a night out gone wild. Few realize that Alcohol Dependence Syndrome is a chronic medical condition that quietly reshapes the brain, sometimes years after the last drink.

What exactly is Alcohol Dependence Syndrome?

Alcohol Dependence Syndrome is defined by the DSM‑5 as a pattern of alcohol use that leads to significant impairment or distress, characterized by tolerance, withdrawal, and loss of control over drinking. In plain language, it means the body and mind have adapted to alcohol to the point where stopping becomes painful and cravings dominate daily life.

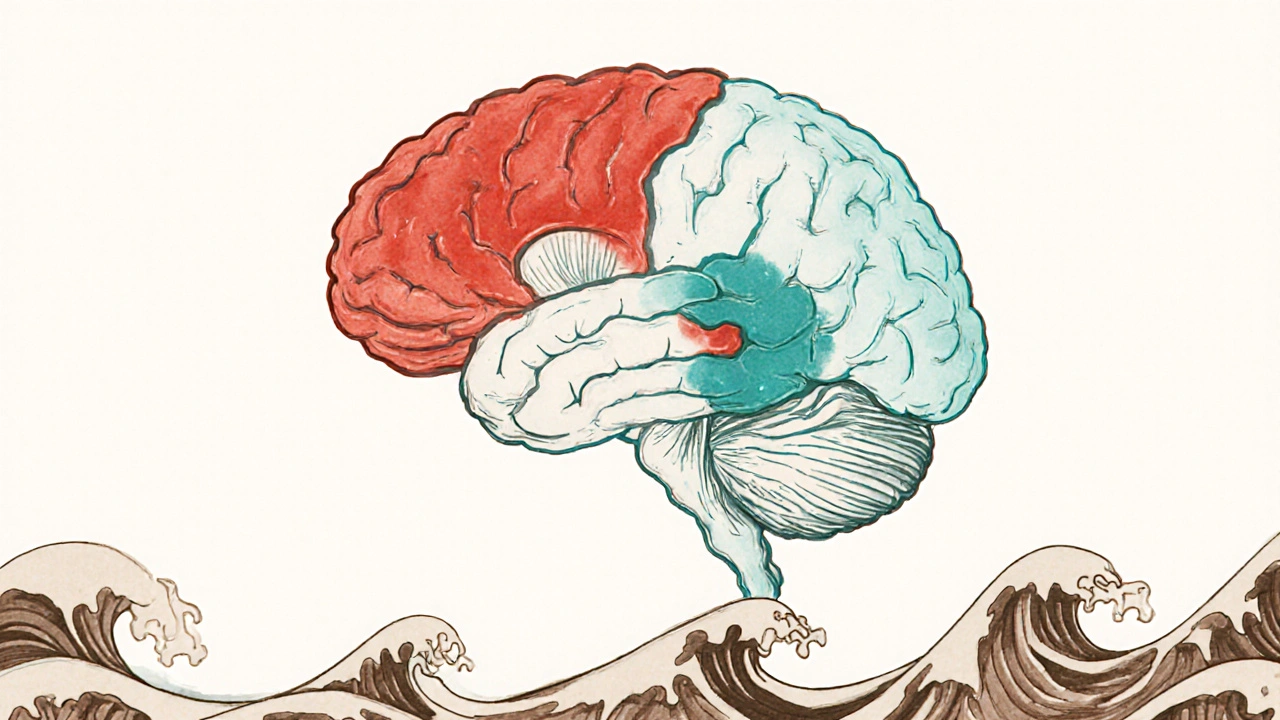

Why does the brain change?

Alcohol is a potent Neurotransmitter modulator that alters the balance between excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA) signals. Repeated exposure forces neurons to compensate-down‑regulating receptors, reshaping synaptic connections, and, over time, shrinking critical structures like the Hippocampus the memory‑forming region of the brain. These neurochemical shifts don’t reset instantly; they persist long after sobriety, setting the stage for cognitive decline.

Cognitive domains most vulnerable to long‑term alcohol use

- Executive function: planning, decision‑making, and impulse control become sluggish.

- Working memory: holding information in mind for short periods feels like juggling water.

- Learning and long‑term memory: forming new memories or recalling past events is unreliable.

- Visuospatial abilities: judging distances or interpreting maps can be off‑kilter.

- Processing speed: mental tasks that once took seconds now stretch into minutes.

Research from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) shows that each of these areas can lose 0.2-0.5 standard deviations of performance after 10+ years of dependence.

Timeline of cognitive change

- First 1-2 years: subtle slowing of reaction time; mild forgetfulness that’s often blamed on stress.

- 3-7 years: noticeable gaps in executive control; difficulty multitasking at work.

- 8+ years: pronounced memory lapses, reduced problem‑solving ability, and increased risk of dementia‑like syndromes.

Even after abstinence, some deficits linger. A 2023 longitudinal study found that 30 % of participants who remained sober for five years still scored below age‑adjusted norms on the Stroop test, a classic measure of executive function.

How clinicians assess the impact

Doctors combine neuropsychological batteries with imaging tools. The most common tests include:

- Mini‑Mental State Examination (MMSE) a quick screen for overall cognitive status

- Trail Making Test measures processing speed and flexibility

- Wechsler Memory Scale assesses short‑ and long‑term memory capacity

Imaging adds another layer. MRI scans often reveal reduced Hippocampal Volume which correlates with memory performance, while PET scans can show diminished glucose metabolism in frontal lobes-a hallmark of executive dysfunction.

Mitigation and recovery strategies

Good news: the brain can bounce back, but the extent depends on age, duration of dependence, and the presence of co‑morbidities (e.g., liver disease, depression).

| Intervention | Typical Duration | Cognitive Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Abstinence | 6-12 months | 10‑15 % improvement in processing speed |

| Cognitive Rehabilitation | 3‑6 months (weekly) | 20‑30 % boost in working memory |

| Physical Exercise | Ongoing | 5‑10 % rise in executive function |

Key tactics include:

- Structured sobriety programs: 12‑step groups or medically‑assisted detox provide the stability needed for neuroplastic recovery.

- Cognitive training: computer‑based tasks that target memory and attention can rewire neural pathways.

- Exercise and nutrition: aerobic activity boosts brain‑derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), while omega‑3‑rich foods protect neuronal membranes.

- Managing comorbidities: treating depression or sleep apnea reduces additional cognitive strain.

Real‑world examples

John, a 48‑year‑old accountant, drank heavily for 15 years. After a liver‑related hospitalization, he entered a rehabilitation program and stayed sober for three years. Neuropsych testing showed a 12 % rise in executive scores, yet his episodic memory remained 8 % below baseline-a reminder that some domains recover slower than others.

Maria, 35, stopped drinking after a decade of binge episodes. She combined abstinence with weekly memory‑training apps. Within a year, her MMSE score climbed from 26 to 29, and she reported feeling “sharper” at work.

Bottom line

Long‑term alcohol dependence does more than damage the liver; it creates a cascade of neurochemical changes that chip away at cognitive function. Early detection, sustained sobriety, and targeted rehabilitation can halt or even reverse many of these effects, but the sooner the intervention, the better the brain’s chances of healing.

Can occasional binge drinking cause the same cognitive decline?

Binge episodes create spikes in blood‑alcohol levels that temporarily impair memory and attention. Repeated binges over years can produce a pattern of damage similar to chronic dependence, especially in the frontal lobes.

Is brain imaging necessary for diagnosis?

Imaging isn’t required for a clinical diagnosis of Alcohol Dependence Syndrome, but it helps quantify the extent of neuro‑degeneration and guides rehabilitation planning.

How long does it take for memory to improve after quitting?

Most studies show noticeable gains in working memory after 6‑12 months of abstinence, while full recovery of episodic memory can take several years, if it recovers at all.

Do genetics influence susceptibility?

Yes. Variants in genes like ADH1B and ALDH2 affect alcohol metabolism, and polymorphisms in the BDNF gene can modulate neuroplasticity, making some people more vulnerable to cognitive loss.

Is there a point of no return?

When structural brain damage becomes extensive-such as severe hippocampal atrophy-reversal is limited. Early intervention before this threshold greatly improves outcomes.

Kate McKay

October 20, 2025 AT 14:07Hey, great rundown on how chronic drinking reshapes the brain. If you or someone you know is starting to notice those subtle memory hiccups, reaching out for a structured sobriety program can make a huge difference. Pairing that with regular exercise and a brain‑training app often speeds up the recovery of processing speed. Keep sharing these insights – they help a lot of folks stay motivated on the long road.

Vijaypal Yadav

October 25, 2025 AT 05:14The neuroadaptations you described hinge on homeostatic plasticity in glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses. Chronic exposure down‑regulates NMDA receptors while up‑regulating GABA_A subunits, forcing the brain into a new equilibrium. This shift explains the persistent executive deficits even after months of abstinence. Moreover, the hippocampal volume loss observed on MRI correlates with reduced neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, as documented in several longitudinal studies. So the mechanistic basis is well‑established, not merely anecdotal.

Ron Lanham

October 29, 2025 AT 19:21Alcohol dependence is not just a personal weakness; it is a societal blight that erodes the very fabric of our communities. When individuals choose to drown their responsibilities in a bottle, they jeopardize their families, their workplaces, and the tax base that funds public services. The brain changes you outlined are the neurobiological fingerprints of that self‑destruction, a clear indication that the habit is no longer a casual pastime but a pathological hijack. It is unforgivable that we continue to romanticize binge nights when the data show irreversible damage in the hippocampus and frontal lobes. Each drop of liquor consumed is a tiny act of betrayal against future generations who will bear the costs of increased healthcare and lost productivity. The moral imperative is therefore crystal clear: we must enforce stricter regulations on alcohol advertising, increase taxes, and fund early‑intervention programs. People often argue that responsible drinking is a matter of personal freedom, yet that freedom does not extend to the right to impair one’s cognitive faculties permanently. Studies cited by the NIAAA demonstrate that even moderate, sustained use can shave off critical years of high‑functioning cognition. It is not enough to tell a friend “just cut back”-the brain’s chemistry rewires in such a way that cutting back becomes almost as hard as quitting cold turkey. Hence, community leaders, healthcare providers, and policy makers must coordinate to make sobriety a reachable norm rather than a fringe lifestyle. Expanding access to cognitive rehabilitation and subsidizing gym memberships for recovering individuals are practical steps that can accelerate neural recovery. Until we collectively recognize that alcohol dependence is a public health emergency, we will continue to watch the slow decay of minds across the nation. The choice is ours: maintain the status quo or act decisively to protect the intellectual capital of our society. We owe it to our children to model disciplined, sober living. Only then can we hope to reverse the tide of cognitive decline that has settled over too many households.

Deja Scott

November 3, 2025 AT 10:27The data you present align with what we see in many cross‑cultural studies: alcohol‑related cognitive decline is a universal phenomenon, not confined to a single demographic. It underscores the importance of tailoring rehabilitation programs to respect cultural attitudes toward drinking. Sharing this knowledge helps break the stigma that often surrounds addiction in diverse communities.

Natalie Morgan

November 8, 2025 AT 01:34Start a brain‑training app today and watch those memory scores climb.

Mahesh Upadhyay

November 12, 2025 AT 16:41So you think a few workouts will fix everything? Reality bites-most people relapse within weeks.

Rajesh Myadam

November 17, 2025 AT 07:47I hear you on the synaptic rewiring-it's a heavy truth to swallow. For anyone battling this, knowing the exact mechanisms can actually empower them to seek targeted therapies. Cognitive rehab combined with mindfulness has shown promise in re‑balancing those glutamate‑GABA loops. Keep the conversation going; understanding breeds hope.

Andrew Hernandez

November 21, 2025 AT 22:54Your call for policy change is noted; practical steps at the community level are essential.

Alex Pegg

November 26, 2025 AT 14:01While cultural factors matter, attributing brain shrinkage solely to drinking ignores genetics and socioeconomic stressors. Blaming alcohol alone is an oversimplification that can mislead public health efforts. A balanced view demands we examine all contributing variables.

laura wood

December 1, 2025 AT 05:07That quick tip could be a game‑changer for someone feeling stuck; small habits really add up over time.

Wesley Humble

December 5, 2025 AT 20:14From a neuropsychological standpoint, the presented longitudinal metrics conform to established variance thresholds in the literature. The reported 0.2‑0.5 standard deviation decline aligns with meta‑analytic effect sizes observed in cohorts exceeding ten years of dependence. Moreover, the integration of MMSE, Trail Making, and Wechsler scales provides a robust composite index for monitoring recovery trajectories. Imaging modalities, specifically volumetric MRI, should be quantified using automated segmentation to ensure reproducibility across sites. It is advisable to augment these assessments with diffusion tensor imaging to elucidate white‑matter integrity post‑sobriety. Ultimately, a multimodal approach maximizes detection sensitivity and informs individualized rehabilitation protocols 😊.