When a generic drug hits the pharmacy shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy. But behind that simple label is a rigorous, science-driven process that ensures it works exactly like the brand-name version. This process is called a bioequivalence study. It’s not guesswork. It’s not marketing. It’s a tightly controlled clinical experiment that measures how your body absorbs a drug - down to the last nanogram per milliliter of blood.

Why Bioequivalence Matters

Before a generic drug can be sold, regulators like the U.S. FDA, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Japan’s PMDA demand proof that it behaves the same way in the body as the original brand-name drug. This isn’t about ingredients being identical on paper - it’s about whether those ingredients end up in your bloodstream at the same speed and in the same amount. Think of it like two identical cars driving the same route. One is a brand-new model, the other a knockoff. You don’t care if the paint is different. You care if they both get to the destination at the same time, using the same amount of fuel. Bioequivalence studies measure exactly that: how fast and how much of the drug enters your blood, and how long it stays there. The stakes are high. The FDA estimates that generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.68 trillion between 2010 and 2019. But that savings only works if the drugs are truly equivalent. A study that fails could mean a patient gets too little of the drug - and the condition worsens - or too much - and they suffer side effects. That’s why the process is so strict.The Gold Standard: Crossover Design

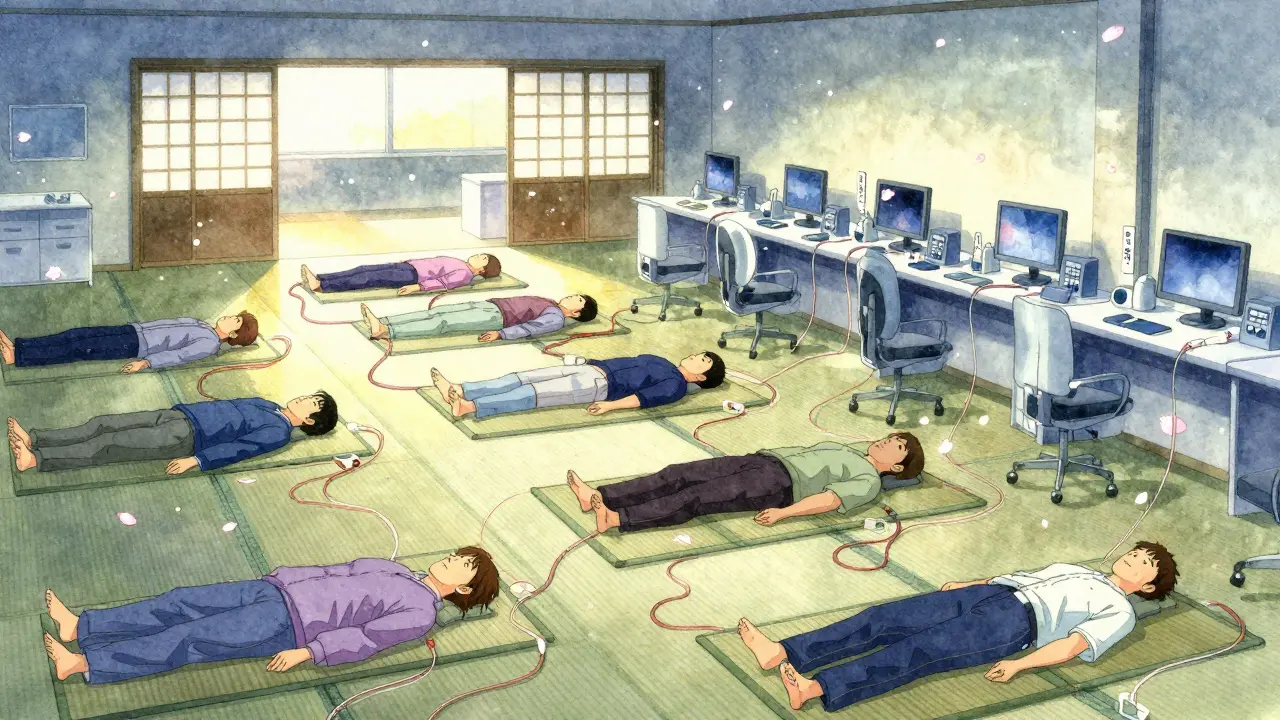

Most bioequivalence studies use a two-period, two-sequence crossover design. That sounds complicated, but here’s how it works in plain terms:- 24 to 32 healthy volunteers (sometimes more, depending on the drug) are enrolled.

- Half get the generic drug first, then after a break, the brand-name drug.

- The other half get the brand-name drug first, then the generic.

How Blood Samples Are Taken

After each dose, volunteers give blood samples at specific times. These aren’t random. They’re carefully planned to capture the full story of the drug’s journey in the body. The sampling schedule typically includes:- A baseline sample before the drug is given (time zero).

- One sample just before the peak concentration (Cmax).

- Two samples around the peak - to catch the rise and fall.

- Three or more samples during the elimination phase, until the drug level drops below detectable limits.

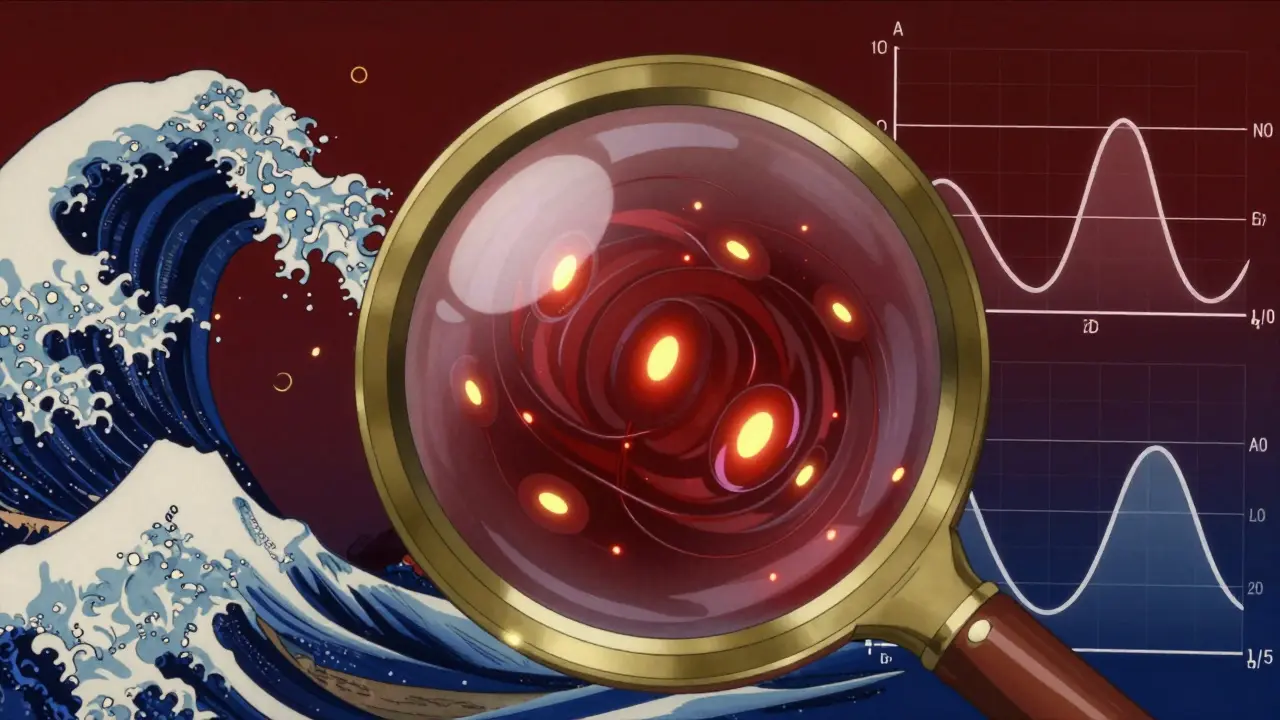

The Two Key Numbers: Cmax and AUC

Two metrics determine success:- Cmax: The highest concentration of the drug in the blood. This tells you how fast the drug is absorbed.

- AUC(0-t): The area under the concentration-time curve from time zero to the last measurable point. This tells you how much of the drug was absorbed overall.

The Acceptance Rule: 80%-125%

Here’s the golden rule: the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of test to reference must fall between 80.00% and 125.00% for both Cmax and AUC. That means:- If the generic delivers 95% of the brand’s Cmax and 102% of its AUC - it passes.

- If it delivers 78% of Cmax - it fails.

- If it delivers 126% of AUC - it fails.

What Happens If the Drug Is Highly Variable?

Some drugs behave wildly differently from person to person. Their within-subject coefficient of variation (CV) exceeds 30%. For these, the standard crossover design lacks power. Regulators have adapted:- The FDA allows reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts the acceptance range based on how variable the reference drug is.

- The EMA requires a four-period replicate crossover design - where each subject gets both drugs twice - to better estimate variability.

- These studies often need 50 to 100 subjects instead of 24-32.

Other Study Types: When PK Isn’t Enough

Not all drugs can be measured by blood levels. For topical creams, inhalers, or injectables that act locally, you can’t just rely on plasma concentration. In those cases, regulators allow alternative approaches:- Pharmacodynamic studies: Measure a biological effect. For example, a generic blood thinner might be tested by measuring clotting time.

- Clinical endpoint studies: Measure actual patient outcomes. This is required for some dermatological products - you don’t just check if the drug gets into the skin, you check if the rash clears.

- In vitro dissolution testing: For certain drugs (BCS Class I), if the tablet dissolves at the same rate as the brand in lab conditions, regulators may waive the human study entirely. This applies to about 27% of 2022 approvals.

Real-World Challenges

Even with perfect science, things go wrong. Contract research organizations (CROs) report:- 45% of failed studies are due to inadequate washout periods.

- 30% fail because sampling times were off - missing the peak or not going long enough.

- 25% have statistical errors - using the wrong model or misinterpreting confidence intervals.

What Makes a Study Valid?

It’s not just about the data. Documentation matters. Every study must include:- A detailed protocol following ICH E9 and E10 guidelines.

- Full validation reports for the analytical method (per FDA Bioanalytical Method Validation Guidance).

- A pre-specified statistical analysis plan - not changed after seeing the results.

- Proof that the test product was made at commercial scale - at least 1/10 of production volume or 100,000 units, whichever is larger.

- Dissolution testing across pH levels (1.2 to 6.8) with an f2 similarity factor above 50.

How Long Does It Take?

A single bioequivalence study can take 6 to 12 months from design to approval:- 3-6 months for protocol development, ethics approval, and site setup.

- 2-4 months for subject recruitment and dosing.

- 2-3 months for lab analysis and data cleaning.

- 2-4 months for statistical analysis and regulatory submission.

What’s Changing?

The field is evolving. New tools are emerging:- Model-informed drug development: Using computer simulations (PBPK models) to predict how a drug will behave - reducing the need for human studies.

- Expanded biowaivers: More drugs qualify for dissolution-only approval based on solubility and permeability (BCS classification).

- Complex products: Guidance is being updated for inhalers, transdermal patches, and long-acting injectables - where traditional methods don’t fit.

Final Thought: It’s Not Magic - It’s Measurement

Bioequivalence studies are not about proving a generic drug is "good enough." They’re about proving it’s the same. Every drop of blood, every hour of sampling, every statistical calculation is there to ensure that when you pick up a generic pill, you’re getting the same therapeutic effect as the brand - at a fraction of the cost. The system isn’t perfect. Mistakes happen. Studies fail. But when done right - with rigor, transparency, and adherence to global standards - bioequivalence is one of the most reliable safeguards in modern medicine.What is the main goal of a bioequivalence study?

The main goal is to prove that a generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. This ensures the generic will have the same therapeutic effect and safety profile.

How many people are needed for a bioequivalence study?

Most studies use 24 to 32 healthy volunteers. For highly variable drugs, the number can increase to 50-100 subjects. The exact number depends on the drug’s pharmacokinetics and regulatory requirements.

Why is the 80%-125% range used for bioequivalence?

This range was established based on statistical and clinical evidence showing that differences within this limit are unlikely to affect therapeutic outcomes. It balances scientific precision with real-world safety, ensuring generics are interchangeable with brand-name drugs.

Can a bioequivalence study be skipped?

Yes, for certain drugs classified as BCS Class I - those that are highly soluble and highly permeable - regulators may allow approval based on in vitro dissolution testing alone. This is called a biowaiver and applies to about 27% of generic approvals.

What happens if a bioequivalence study fails?

If the 90% confidence interval for Cmax or AUC falls outside 80%-125%, the application is rejected. The sponsor must revise the formulation, improve manufacturing, or redesign the study. Failure rates are around 30-35% without pilot testing, but drop below 10% when pilot studies are used.

Are bioequivalence studies only for oral drugs?

No. While most studies focus on oral drugs, bioequivalence methods are also used for topical creams, inhalers, and injectables. For these, alternative approaches like pharmacodynamic measurements or clinical endpoint assessments are often required because blood levels don’t reflect local drug action.

astrid cook

January 28, 2026 AT 10:56Kirstin Santiago

January 28, 2026 AT 13:19Candice Hartley

January 28, 2026 AT 18:57Kathy McDaniel

January 30, 2026 AT 14:41Paul Taylor

January 31, 2026 AT 01:31Desaundrea Morton-Pusey

January 31, 2026 AT 23:45Murphy Game

February 1, 2026 AT 04:02John O'Brien

February 2, 2026 AT 08:33Kegan Powell

February 3, 2026 AT 01:07April Williams

February 3, 2026 AT 21:55Harry Henderson

February 4, 2026 AT 05:45suhail ahmed

February 5, 2026 AT 17:00Andrew Clausen

February 6, 2026 AT 19:45