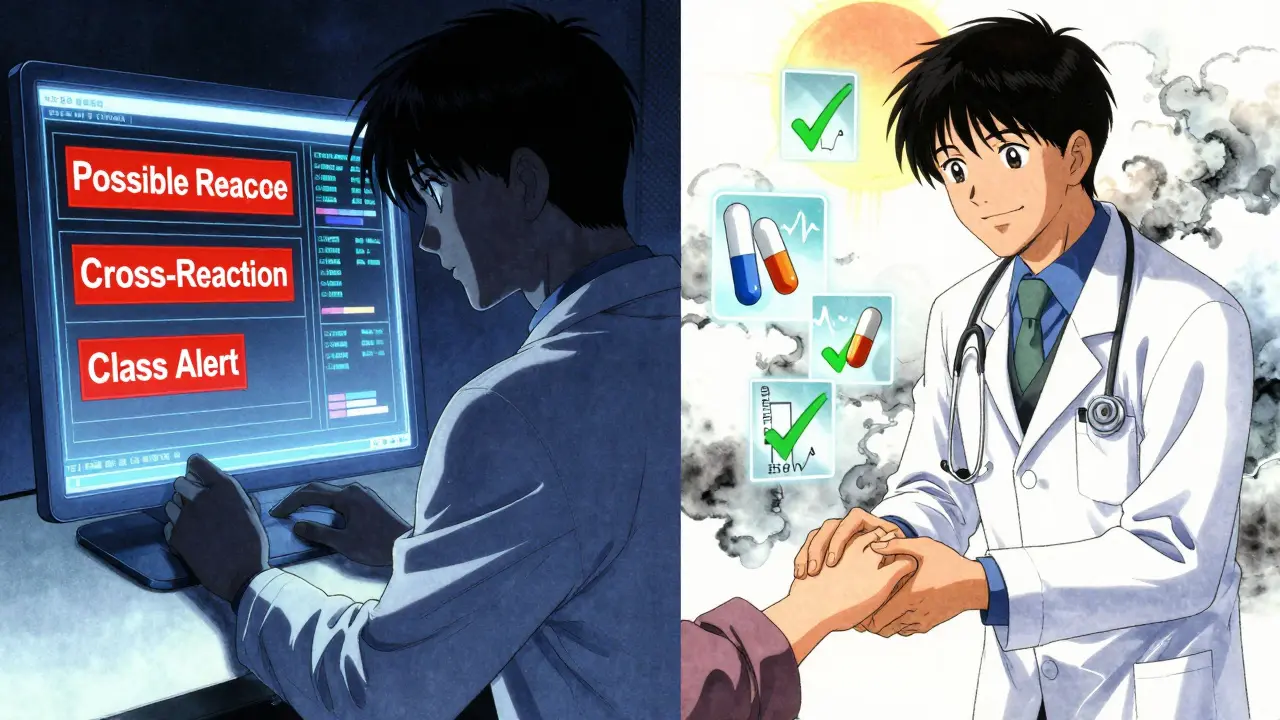

Every time you pick up a prescription, there’s a quiet digital guard watching over it - an allergy alert flashing on the pharmacist’s screen. It might say "Penicillin allergy detected" or "Possible cross-reaction with cephalosporin". You’ve probably seen these pop-ups if you’ve ever filled a script at a chain pharmacy or been treated in a hospital. But what do they really mean? And why do so many seem wrong?

What Is a Pharmacy Allergy Alert?

An allergy alert is a computer-generated warning in a pharmacy or hospital’s electronic system that flags a potential conflict between a prescribed drug and a patient’s recorded allergies. These systems have been around since the early 2000s, built into platforms like Epic and Cerner. Their job is simple: stop a dangerous drug from being given to someone who’s had a bad reaction before.

But here’s the catch - most of these alerts aren’t as clear-cut as they look. They don’t just match the exact drug name. They also scan for entire drug classes. For example, if you’re labeled as allergic to penicillin, the system might block not just penicillin, but amoxicillin, ampicillin, and sometimes even unrelated antibiotics like cephalexin - even if you’ve taken those safely for years.

Definite vs. Possible Allergy Alerts

Not all alerts are created equal. There are two main types:

- Definite allergy alerts - These happen when the drug matches exactly or belongs to the same class as something you’ve been documented as allergic to. For example, if you wrote down "allergic to penicillin" and your doctor prescribes amoxicillin, you’ll get a strong warning.

- Possible allergy alerts - These are based on cross-reactivity assumptions. The system guesses you might react because two drugs are "similar." This is where things get messy. Most alerts - about 90% - fall into this category.

A 2020 study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice found that clinicians misinterpret these differences nearly half the time. Many assume a "possible" alert means the same risk as a "definite" one. That’s not true.

Why So Many Alerts Are Wrong

Let’s say you had a stomach ache after taking amoxicillin as a kid. You told your doctor, "I’m allergic to penicillin." That got logged. Now, decades later, you’re being treated for a sinus infection. The system blocks azithromycin because it’s "in the same family" - even though it’s not. This happens all the time.

Here’s the hard truth: More than half of all allergy alerts are triggered by reactions that weren’t true allergies at all. A 2021 editorial in JAMA Internal Medicine found that many patients were labeled allergic based on side effects like nausea, dizziness, or headaches - none of which involve the immune system.

True drug allergies involve your immune system reacting to a drug like it’s a virus. Symptoms include hives, swelling, trouble breathing, or anaphylaxis. But most reactions people call "allergies" are just side effects. That’s why 75-82% of severe allergy alerts get overridden by doctors and pharmacists - not because they’re careless, but because they’ve seen too many false alarms.

How EHR Systems Get It Wrong

Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems use commercial databases like First DataBank to decide what counts as a cross-reaction. These databases were built decades ago using outdated science. For example, many still assume that if you’re allergic to penicillin, you’re likely allergic to cephalosporins. But research from the Cochrane Review in 2019 showed that cross-reactivity between penicillin and later-generation cephalosporins is less than 2% - not the 10% many systems still assume.

Even worse, many systems don’t ask for details. They just say "allergy." No severity. No description. No date. That’s why one pharmacist told me about a patient flagged for a "penicillin allergy" after a childhood stomachache - the system didn’t know the reaction was mild and non-immune.

Some systems are better than others. Epic’s newer versions use "Allergy Relevance Scoring," a machine learning tool that learns from past overrides. If 90% of doctors ignore a certain alert, the system starts lowering its priority. Cerner’s new "Precision Allergy" module pulls in data from allergist visits to automatically remove alerts if a patient has been tested and cleared.

What You Should Look For

When you see an allergy alert, don’t panic. Ask these four questions:

- What was the reaction? Was it a rash? Nausea? Trouble breathing? Only immune-driven reactions like hives, swelling, or anaphylaxis count as true allergies.

- When did it happen? True allergic reactions usually show up within minutes to hours after taking the drug. If you got sick a day later after a 10-day course, it’s likely not an allergy.

- Is this a class alert? Is the system blocking the whole class? Penicillin, cephalosporin, sulfa? Many drugs in the same class are completely safe for people with mild reactions.

- Was it ever confirmed? Did you ever get tested? Most people labeled "allergic" never had a skin test or oral challenge. That label might be wrong.

A 2022 study at Johns Hopkins showed that when patients were asked to describe their reactions in detail during check-ups, accurate allergy documentation jumped from 39% to 76% in just six months.

What Pharmacists and Doctors Are Doing About It

Health systems are slowly fixing the problem. The 21st Century Cures Act, effective January 1, 2023, now requires EHRs to support detailed allergy documentation - not just "allergy" but the exact reaction, severity, and date.

Some hospitals now require pharmacists to call patients before dispensing a flagged drug. Others use patient portals to let people update their own allergy lists with more detail. Mayo Clinic’s system reduced false alerts by 44% after they started asking patients: "What happened when you took this drug?" instead of just checking a box.

Even the biggest vendors are changing. Epic’s 2023 update uses AI to predict which alerts are most likely to be relevant. Oracle Health (formerly Cerner) now integrates with allergist records. The NIH-funded ALERT-ASAP study found that when clinicians had to pick a reaction type and severity, unnecessary alerts dropped by 51% - without missing a single real danger.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t have to wait for the system to fix itself. Here’s what you can do:

- Review your allergy list every time you see a doctor. Don’t just say "I’m allergic to penicillin." Say, "I got a rash after amoxicillin when I was 8 - no breathing problems, no swelling. Never had a reaction since."

- Ask if you’ve ever been tested. If you’ve been told you’re allergic to penicillin, ask your doctor about a penicillin skin test. It’s quick, safe, and about 90% accurate. Many people who think they’re allergic aren’t.

- Use your patient portal. If your pharmacy or hospital lets you update your medical record online, do it. Add details. Remove outdated labels.

- Don’t assume an alert is always right. If you’ve taken a drug before without issue, say so. Your history matters more than a computer’s guess.

One woman in Bristol told me she’d avoided all NSAIDs for 15 years because she once got a headache after ibuprofen. She finally asked her pharmacist to check. Turns out, headaches aren’t an allergy. She now takes naproxen safely for her arthritis - no issues.

Why This Matters

These alerts aren’t just annoying. They’re dangerous - but not because they’re too strict. They’re dangerous because they’re too loose.

When a system blocks a safe drug because of a false alert, doctors reach for something else - often a broader-spectrum antibiotic or a more expensive drug. That increases resistance, side effects, and costs. A 2019 study in Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology found that only 12% of NSAID allergy alerts were clinically meaningful. The rest? Waste.

On the flip side, when a real allergy alert gets overridden because of alert fatigue, someone could end up in the ER with anaphylaxis. That’s why the NIH recommends a new approach: risk-stratified alerting. Severe, immune-mediated reactions get loud, mandatory warnings. Mild reactions get quiet notes. Cross-reactivity alerts get flagged only when the risk is real - not assumed.

By 2026, 70% of major EHR systems are expected to use this smarter model, according to Gartner. But until then, you’re your own best defense.

Final Takeaway

Pharmacy allergy alerts are meant to protect you. But they’re built on outdated rules and incomplete data. Don’t treat them like gospel. Treat them like a starting point. Your history, your symptoms, your questions - those matter more than any algorithm.

If you’ve been told you’re allergic to a drug, ask: "Was this ever confirmed?" If you’ve had a reaction, describe it - not just the drug, but what happened, how bad it was, and when. You might be surprised. You might be safe. And you might just save yourself from years of unnecessary restrictions.

What’s the difference between a drug allergy and a side effect?

A drug allergy involves your immune system reacting to the medication, causing symptoms like hives, swelling, trouble breathing, or anaphylaxis. A side effect is a non-immune reaction - like nausea, dizziness, or headache - that doesn’t mean your body is attacking the drug. Most people who think they’re allergic to a drug are actually experiencing a side effect.

Can I outgrow a drug allergy?

Yes, especially with penicillin. About 80% of people who had a penicillin allergy as a child lose it within 10 years - even if they never got tested. The label stays in your record, but your body may no longer react. A simple skin test can confirm if you’re still allergic.

Why do I get alerts for drugs I’ve taken before without problems?

Because the system doesn’t know your full history. It only sees what’s documented. If you once had a stomach ache after amoxicillin and called it an "allergy," the system flags every penicillin-class drug - even if you’ve taken them safely since. That’s why it’s critical to update your allergy list with details, not just labels.

Are cephalosporins safe if I’m allergic to penicillin?

For most people, yes. Cross-reactivity between penicillin and later-generation cephalosporins (like ceftriaxone or cefdinir) is less than 2%, according to the Cochrane Review. Many systems still block them out of caution, but the risk is extremely low. If you’ve tolerated a cephalosporin before, it’s almost certainly safe.

Can I ask my pharmacist to check my allergy alert?

Absolutely. Pharmacists are trained to interpret these alerts. If you’re unsure why a drug is being blocked, ask them to explain the reason. They can often override the alert if you provide details about your past reaction - especially if you’ve taken the drug safely before.

Should I get tested for drug allergies?

If you’ve been told you’re allergic to penicillin or another common drug - and you’ve taken it since without issues - yes. Skin tests or oral challenges are safe, quick, and can remove unnecessary restrictions. It’s one of the most underused tools in modern medicine.