Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Assessment Tool

How to Use This Tool

This assessment helps determine if you might be experiencing opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH). Answer the questions honestly based on your symptoms and opioid use history. Remember: OIH is different from tolerance. If you score high risk, consult your doctor for proper diagnosis.

Assessment Result

What if taking more opioids to relieve your pain actually made it worse? It sounds impossible, but it happens. This isn’t a myth or a misunderstanding-it’s a real, documented condition called opioid-induced hyperalgesia. And it’s more common than most doctors and patients realize.

What Exactly Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

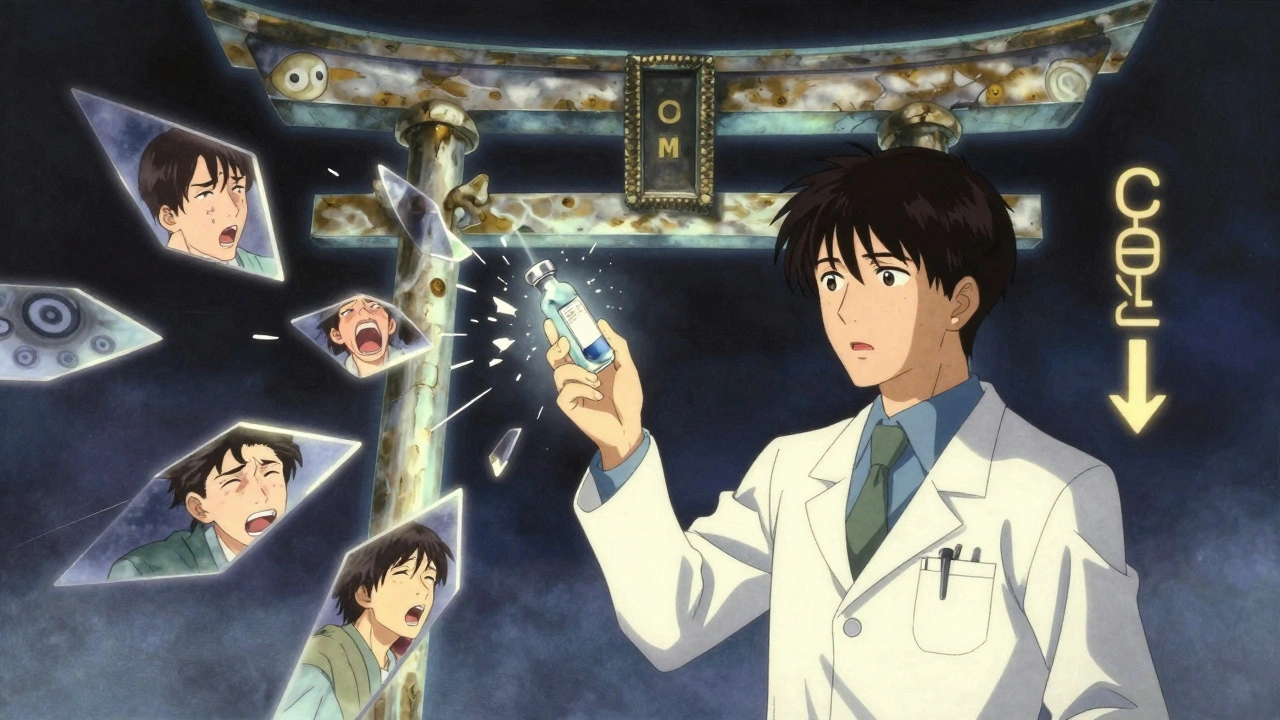

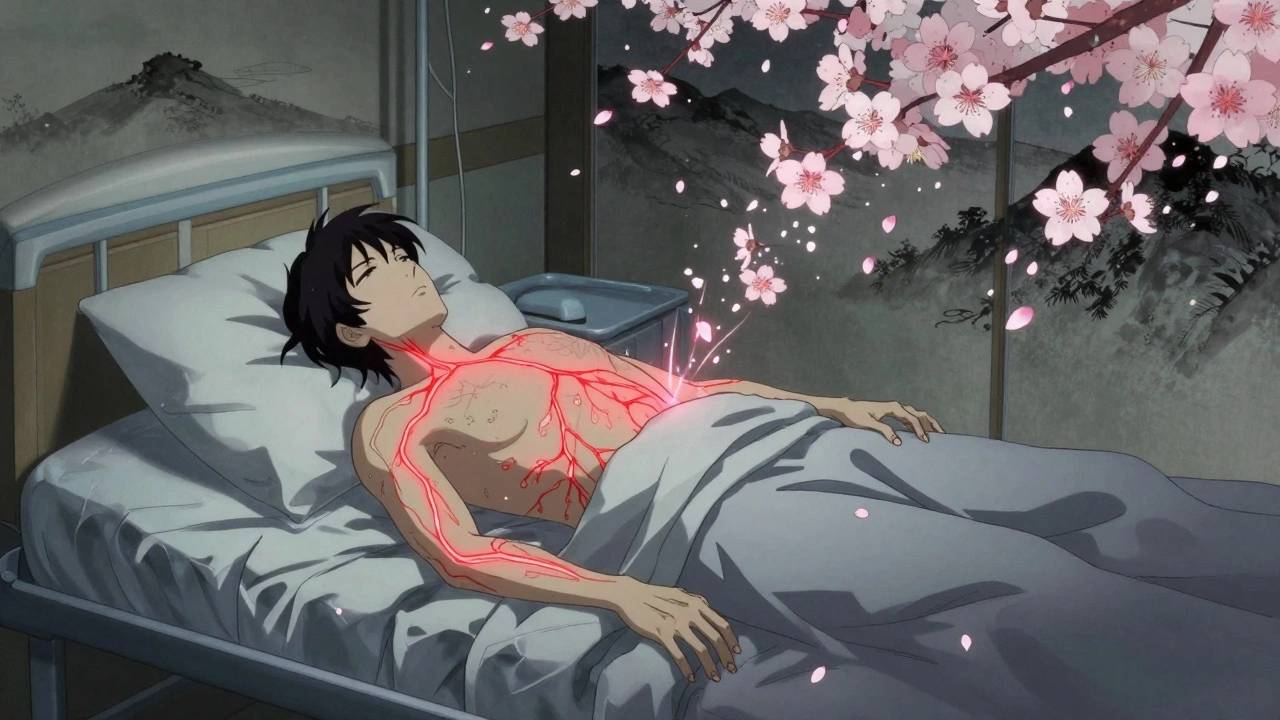

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) is when long-term opioid use causes your nervous system to become oversensitive to pain. Instead of calming your pain, the drugs start amplifying it. You might notice that even light touches-like sheets against your skin-hurt. Or that pain spreads to areas where it never existed before. And no matter how much you increase your dose, the pain keeps climbing. This isn’t tolerance. Tolerance means you need higher doses to get the same pain relief. OIH means your body is now generating more pain than before you started opioids. It’s like turning up the volume on a speaker until the music turns into static-except here, the static is your own pain signals. The first signs showed up in animal studies back in 1971. Researchers gave rats repeated morphine injections and found they became more sensitive to heat and pressure. Since then, dozens of human studies have confirmed it. People on long-term opioids for back pain, cancer pain, or even post-surgery discomfort can develop this paradoxical reaction. It doesn’t matter if you’re on low or high doses-it can happen at any level, though it’s more common with strong opioids like morphine, hydromorphone, or fentanyl, especially in people with kidney problems.How Is It Different From Tolerance?

This is where things get confusing. Most people assume that if pain gets worse and you need more pills, it’s just tolerance. But tolerance and OIH are completely different. - Tolerance: Your body adapts to the drug. You need more to feel the same effect. The pain itself hasn’t changed-just your response to the medication. - OIH: Your nervous system rewires itself to feel more pain. You might be getting the same level of pain relief from the opioid, but your baseline pain has gotten worse. You now hurt from things that never hurt before. A key clue? Allodynia. That’s when something harmless-like a breeze, a hug, or even a shirt tag-triggers sharp pain. That’s not typical pain. That’s your nerves screaming. It’s a red flag for OIH. Another clue: pain that spreads. If your original back pain now includes your legs, arms, or even your head, that’s a sign your nervous system is overactive. Not just the injury talking-your brain and spinal cord are now the problem.What Causes Your Body to Turn Against You?

OIH isn’t random. It’s a biological cascade triggered by opioids themselves. Here’s how it works: 1. NMDA receptors wake up. Opioids bind to μ-receptors, which accidentally turn on NMDA receptors in your spinal cord. These receptors are usually quiet, but when activated, they flood your system with pain signals. This is the most well-studied pathway. 2. Dynorphin spikes. Your body releases this neuropeptide in response to opioids. Dynorphin doesn’t calm pain-it makes it worse. It’s like your body trying to fight the drug by turning up the pain dial. 3. Descending facilitation kicks in. Normally, your brain sends signals down the spine to dampen pain. With OIH, those signals flip. Instead of turning pain down, they turn it up. The rostral ventromedial medulla-a brain region meant to control pain-becomes a pain amplifier. 4. Metabolites pile up. Opioids like morphine break down into substances like morphine-3-glucuronide. These leftover chemicals are toxic to nerve cells. In people with kidney issues, these build up and directly irritate nerves. 5. Your genes play a role. Some people are more vulnerable because of variations in the COMT gene. This gene controls how quickly your body breaks down dopamine and norepinephrine. If your version is slow, your pain system stays wired on high. That’s why two people on the same dose can have totally different outcomes. It’s not one thing-it’s a perfect storm of biology, chemistry, and genetics.

Why Is It So Hard to Diagnose?

Doctors don’t miss OIH because they’re careless. They miss it because it looks like everything else. - Is the pain getting worse because the cancer is spreading? - Is it withdrawal? Opioid withdrawal can cause pain too. - Is it psychological? - Or is it just tolerance? There’s no blood test. No scan. No single symptom that screams “OIH.” Diagnosis is based on patterns:- Pain worsens despite increasing opioid doses

- Pain becomes more widespread, not just in the original area

- Allodynia appears-light touch hurts

- No new injury or disease explains the change

What Can You Do If You Suspect OIH?

The good news? You can fix it. But it requires a careful, step-by-step approach. You can’t just stop opioids cold. That can trigger severe withdrawal and make things worse. Here’s what actually works: 1. Reduce the dose slowly. This sounds counterintuitive-less pain medicine to treat more pain? But studies show that lowering the opioid dose often reduces overall pain. Why? Because you’re removing the trigger that’s making your nerves hypersensitive. 2. Switch opioids (rotation). Not all opioids are the same. Methadone is a game-changer here. It blocks NMDA receptors-the same ones that cause OIH. So when you switch from morphine to methadone, you’re not just changing drugs-you’re hitting the reset button on your nervous system. One study showed patients needed 40% less pain medication after switching. 3. Add non-opioid blockers.- Ketamine: A low-dose IV infusion (0.1-0.5 mg/kg/hour) can quiet overactive NMDA receptors. Used in hospitals for severe cases.

- Gabapentin or pregabalin: These calm overactive nerves by targeting calcium channels. Doses range from 900-3600 mg/day for gabapentin, 150-600 mg/day for pregabalin.

- Magnesium sulfate: Given intravenously, it acts like a natural NMDA blocker. Often used in post-op settings.

What About Long-Term Use? Should You Avoid Opioids Altogether?

No. Opioids still have a vital place in medicine. For someone with terminal cancer, they’re life-changing. For acute pain after surgery, they’re essential. The problem isn’t opioids themselves. It’s using them long-term for chronic non-cancer pain without understanding the risks. The evidence is clear: for conditions like chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, or osteoarthritis, opioids offer little long-term benefit-and carry a high risk of OIH, addiction, and overdose. The CDC and American Pain Society now recommend opioids only as a last resort for chronic pain. And even then, they should be used at the lowest effective dose for the shortest time possible.What’s Next for OIH Research?

Scientists are working on better tools to spot OIH early. One promising area is quantitative sensory testing-measuring how sensitive your skin is to heat, cold, or pressure. If your pain threshold drops in areas far from your original injury, that’s a strong indicator. Researchers are also testing new drugs that block pain without triggering hyperalgesia. Kappa-opioid agonists, for example, seem to relieve pain without activating the NMDA pathway. And genetic screening for COMT variants might one day help doctors predict who’s at highest risk before they even start opioids. But for now, the best tool is awareness. If you’ve been on opioids for more than a few months and your pain is getting worse-not better-it’s time to ask the question: Could this be OIH?Frequently Asked Questions

Can opioid-induced hyperalgesia happen with low-dose opioids?

Yes. While it’s more common with high doses or intravenous use, OIH can develop even at low oral doses over time. The risk increases with duration-not just dosage. Someone on 20 mg of oxycodone daily for two years can develop OIH just as easily as someone on 100 mg.

Is OIH the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive drug use despite harm, cravings, and loss of control. OIH is a neurological side effect. You can have OIH without being addicted, and you can be addicted without having OIH. But they can happen together, which makes treatment more complex.

How long does it take for OIH to develop?

There’s no fixed timeline. Some patients report symptoms after just a few weeks, especially with high-dose or IV use. Others develop it after months or years. The key factor is cumulative exposure-not how long you’ve been on it, but how much your nervous system has been exposed to opioid-induced changes.

Can OIH be reversed?

Yes, often completely. Many patients see significant pain reduction within weeks of reducing opioids or switching to methadone. Nerve hypersensitivity doesn’t last forever-it’s a learned response. With the right treatment, your nervous system can unlearn it.

Should I stop my opioids if I think I have OIH?

Never stop opioids suddenly. That can cause dangerous withdrawal, worsen pain, and trigger other complications. Talk to your doctor about a safe taper plan. Often, switching to methadone or adding gabapentin can help you reduce opioids gradually without a spike in pain.

Deborah Andrich

December 12, 2025 AT 21:51Jennifer Taylor

December 13, 2025 AT 10:57nithin Kuntumadugu

December 14, 2025 AT 16:35John Fred

December 16, 2025 AT 11:45Harriet Wollaston

December 18, 2025 AT 10:11Lauren Scrima

December 20, 2025 AT 08:06sharon soila

December 21, 2025 AT 07:54Hamza Laassili

December 22, 2025 AT 20:52Tyrone Marshall

December 23, 2025 AT 00:47Alvin Montanez

December 24, 2025 AT 21:32Lara Tobin

December 25, 2025 AT 13:03Keasha Trawick

December 25, 2025 AT 21:55Webster Bull

December 26, 2025 AT 23:38Bruno Janssen

December 27, 2025 AT 18:49