Childhood Cancer Comparison Tool

When doctors talk about Rhabdomyosarcoma is a rare soft‑tissue tumor that originates from skeletal‑muscle precursors and primarily affects children. It’s the most common pediatric soft‑tissue sarcoma, but its story doesn’t end there - the disease shares DNA clues, treatment plans, and even survival challenges with several other childhood cancers.

What Rhabdomyosarcoma Really Is

The tumor can appear in the head‑and‑neck region, the genitourinary tract, or the extremities. Two main subtypes dominate the landscape:

- Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS) - usually diagnosed before age 10 and linked to the PAX3‑FOXO1 fusion gene in a minority of cases.

- Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS) - more common in teenagers, often carrying the PAX7‑FOXO1 fusion and showing a faster growth pattern.

Both forms rely on the same cellular pathways that power muscle development, which is why researchers keep an eye on them when studying other pediatric tumors.

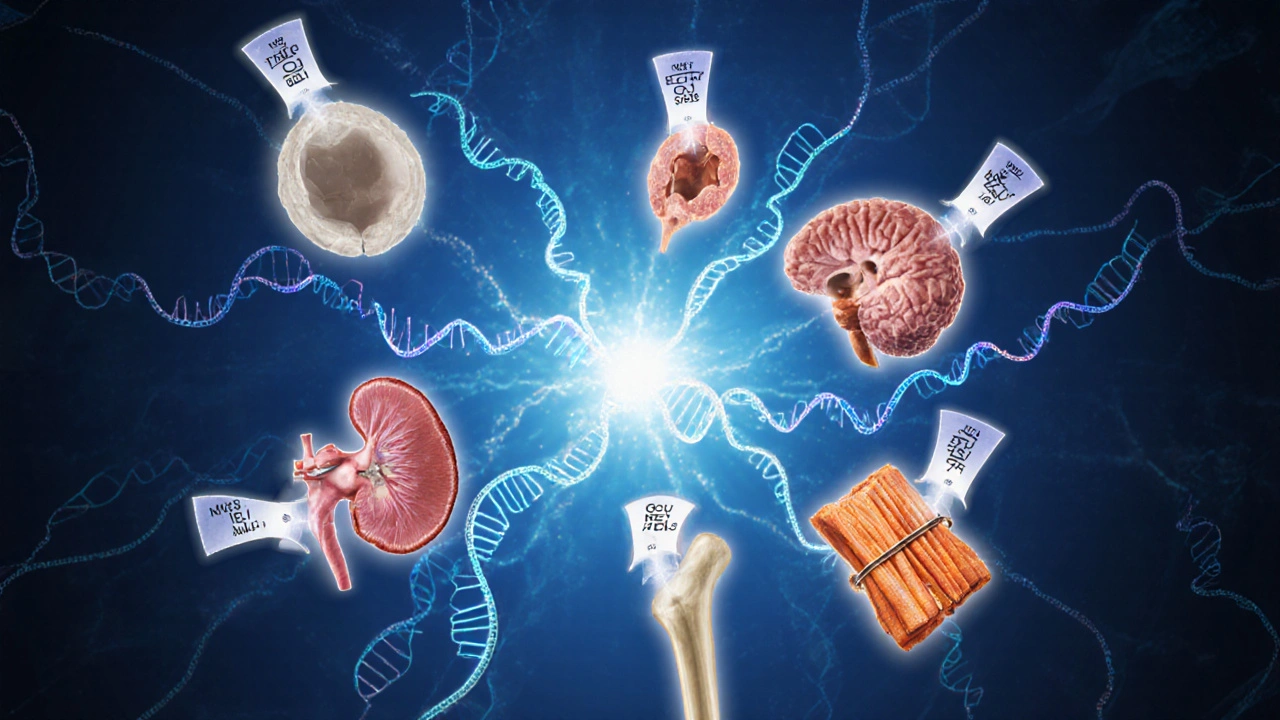

Childhood Cancers That Share Genetic Footprints

Several childhood malignancies have overlapping genetic drivers:

- Neuroblastoma is a nerve‑cell tumor that sometimes harbors MYCN amplification, a driver also seen in a subset of aggressive rhabdomyosarcoma.

- Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) often features the TEL‑AML1 fusion; interestingly, the same signaling cascade can be activated by PAX‑FOXO1 fusions in ARMS.

- Medulloblastoma, a brain tumor, relies on the SHH pathway, which is also a key regulator in early muscle cell differentiation and therefore relevant to rhabdomyosarcoma biology.

- Wilms Tumor frequently shows WT1 mutations; WT1 plays a role in both kidney and muscle development, linking it conceptually to rhabdomyosarcoma.

- Osteosarcoma shares the TP53 loss of function seen in many high‑grade sarcomas, including ARMS.

These shared genes don’t mean the cancers are identical, but they give scientists a common language for developing targeted drugs.

Head‑to‑Head Comparison

| Cancer | Typical Age at Diagnosis | Primary Site | 5‑Year Survival (US, 2023) | Key Genetic Alteration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0‑14 | Head/neck, genitourinary, extremities | 73% | PAX3‑FOXO1 / PAX7‑FOXO1 fusion |

| Neuroblastoma | 0‑5 | Adrenal medulla, sympathetic chain | 71% | MYCN amplification |

| Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | 2‑15 | Bone marrow | 90% | TEL‑AML1, BCR‑ABL1 |

| Medulloblastoma | 3‑10 | Cerebellum | 78% | SHH pathway activation |

| Wilms Tumor | 2‑5 | Kidney | 90% | WT1 mutation |

| Osteosarcoma | 10‑20 | Long bones | 68% | TP53 loss |

The table shows that while rhabdomyosarcoma’s survival rate sits between neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma, the genetic overlap with many of these tumors creates opportunities for shared therapies.

Risk Factors That Cross Tumor Boundaries

Environmental and hereditary factors rarely act alone. Known contributors include:

- Inherited syndromes such as Li‑Fraumeni (TP53) and Beckwith‑Wiedemann (IGF2) - both raise the odds of rhabdomyosarcoma, Wilms tumor, and sometimes neuroblastoma.

- Pre‑birth exposures (e.g., parental smoking, certain chemotherapy agents) - epidemiological studies from 2022‑2024 link these to a modest increase in several childhood cancers.

- Viral infections - the rare association between Epstein‑Barr virus and certain sarcomas hints at a broader immune‑modulation theme that also appears in Hodgkin lymphoma.

Understanding these intersecting risks helps pediatric oncologists flag families for genetic counseling early.

Treatment Strategies That Borrow From Each Other

Multi‑modal therapy-surgery, chemotherapy, radiation-remains the backbone for most pediatric tumors. However, a few cutting‑edge approaches blur the lines:

- Targeted inhibitors such as crizotinib, originally approved for ALK‑positive neuroblastoma, are now in early‑phase trials for ALK‑rearranged rhabdomyosarcoma.

- Immunotherapy with anti‑GD2 antibodies, a staple for high‑risk neuroblastoma, shows promise in pre‑clinical models of RMS because GD2 is expressed on some muscle‑derived sarcoma cells.

- CAR‑T cell platforms targeting HER2 have entered joint protocols for both medulloblastoma and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, reflecting the shared surface antigen.

Clinical trials often enroll patients with different diagnoses under one umbrella, accelerating drug approval for rare cancers like rhabdomyosarcoma.

Survival Outlook and What Influences It

Several factors tilt the odds:

- Stage at diagnosis - localized disease yields >90% 5‑year survival, while metastatic spread drops that below 40%.

- Fusion status - patients with the PAX3‑FOXO1 fusion tend to have a poorer prognosis than those with fusion‑negative tumors.

- Age - infants under one year often experience treatment‑related toxicities that affect long‑term outcomes.

When compared to other childhood cancers, rhabdomyosarcoma’s survival curve mirrors neuroblastoma’s early‑stage success but diverges sharply once the disease spreads.

Quick Checklist for Parents & Clinicians

- Ask about family history of Li‑Fraumeni, Beckwith‑Wiedemann, or other cancer‑predisposition syndromes.

- Request molecular testing for PAX‑FOXO1 fusions and any actionable mutations (e.g., ALK, MET).

- Discuss enrollment in umbrella trials that include multiple pediatric sarcomas.

- Monitor for late effects - radiation to the head/neck can impact growth; regular endocrinology follow‑up is advised.

Staying proactive about genetics and trial options often translates into better long‑term health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is rhabdomyosarcoma hereditary?

A small percentage of cases are linked to inherited cancer‑predisposition syndromes such as Li‑Fraumeni or Beckwith‑Wiedemann. Most children develop the disease sporadically, without a clear family pattern.

Can treatments for other childhood cancers help rhabdomyosarcoma patients?

Yes. Targeted drugs and immunotherapies that were first approved for neuroblastoma, leukemia, or medulloblastoma are now being tested in rhabdomyosarcoma trials, especially when the tumor shares the same molecular target.

What does a PAX‑FOXO1 fusion mean for prognosis?

Presence of the fusion, particularly PAX3‑FOXO1, is associated with a more aggressive tumor and lower survival rates compared to fusion‑negative rhabdomyosarcoma.

Are there screening programs for early detection?

No universal screening exists because the disease is rare. However, children with known genetic syndromes receive periodic imaging and blood work to catch tumors early.

What long‑term side effects should survivors watch for?

Survivors may face growth disturbances, hearing loss (from platinum‑based chemo), cardiac issues, or secondary malignancies. Regular check‑ups with a pediatric oncologist and relevant specialists are essential.

justin davis

October 5, 2025 AT 16:28Rhabdomyosarcoma primarily hits kids aged 0‑14, often in the head, neck, genitourinary tract, or extremities!!! It's the most common pediatric soft‑tissue sarcoma, so yeah, it's a big deal!!! If you thought this was just another boring medical chart, think again!!!

David Lance Saxon Jr.

October 7, 2025 AT 18:28From an oncogenomic perspective, the PAX‑FOXO1 fusion epitomizes a quintessential driver mutation, integrating transcriptional dysregulation with myogenic lineage fidelity; consequently, the phenotypic convergence observed across rhabdomyosarcoma and neuroblastoma underscores a shared oncogenic circuitry that transcends tissue specificity, thereby challenging conventional nosological compartmentalization.

Moore Lauren

October 9, 2025 AT 20:28Key takeaway: early genetic testing can guide risk‑adapted therapy and improve outcomes.

Jonathan Seanston

October 11, 2025 AT 22:28Hey, that's a solid point! It really helps to see how those pathways overlap across different childhood cancers.

Sukanya Borborah

October 14, 2025 AT 00:28Honestly, this tool looks like a half‑baked brochure. The data tables are skimpy, and the UI is clunky – not sure it adds any real value for clinicians.

bruce hain

October 16, 2025 AT 02:28While the presented statistics are accurate, one could argue that focusing solely on survival percentages oversimplifies the nuanced prognostic factors at play.

Stu Davies

October 18, 2025 AT 04:28That makes sense 😊. It’s true that stage, fusion status, and patient age all modulate outcomes.

Nadia Stallaert

October 20, 2025 AT 06:28Listen, the very notion that rhabdomyosarcoma is somehow an isolated anomaly is a delusion propagated by mainstream oncology narratives!!! The genetic undercurrents that tie PAX‑FOXO1 fusions to MYCN amplification suggest a clandestine network of oncogenic conspiracies that the establishment refuses to acknowledge!!! Every time a new study surfaces linking TP53 loss in osteosarcoma to similar pathways in rhabdo, the silence is deafening!!! We must question why funding agencies hide these cross‑cancer insights behind paywalls and jargon!!! Are we truly studying the disease, or are we merely playing with toys in a laboratory while children suffer??? The pattern is clear: inherited syndromes like Li‑Fraumeni create a fertile ground for multiple malignancies, yet the discourse isolates each cancer as a separate entity!!! This compartmentalization serves the interests of pharmaceutical monopolies eager to segment markets!!! Moreover, the survival statistics cited-73% for rhabdo-mask the stark reality that metastatic cases plummet below 20%!!! The data presented in this tool glosses over those grim figures, offering a rosier picture than reality warrants!!! One cannot ignore the pre‑birth exposure hypotheses, which hint at environmental tampering that remains unregulated!!! The whole “risk factor” list feels like a smokescreen, diverting attention from systemic pollutants and corporate negligence!!! In summary, the interconnected genetic landscape demands a unified research approach, not the fragmented silos currently enforced by academic gatekeepers!!! The truth lies hidden, and it's up to us to unveil it!!!

Greg RipKid

October 22, 2025 AT 08:28That's a lot to take in. I see where you're coming from, but some of those claims feel a bit over the top.

John Price Hannah

October 24, 2025 AT 10:28Oh, the drama! The blood runs cold when you realize how many shadows loom over these tiny warriors-yet the world keeps blinking its neon lights, oblivious!!!

Echo Rosales

October 26, 2025 AT 11:28Honestly, this comparison tool is just a marketing gimmick.

Elle McNair

October 28, 2025 AT 13:28I get your frustration, but maybe it could still help families understand options.

Dennis Owiti

October 30, 2025 AT 15:28Ths tool mst hv bn updted, ths is crpnt. Th speeling nd frmttng r off.

Justin Durden

November 1, 2025 AT 17:28Great effort on pulling these stats together! Keep refining the interface and it'll be a real asset for the community.

Sally Murray

November 3, 2025 AT 19:28In contemplating the epistemological framework underpinning pediatric oncologic data aggregation, one discerns a dialectic tension between empiricism and heuristic simplification, which this tool strives to reconcile.

Bridgett Hart

November 5, 2025 AT 21:28The analysis, while articulate, ultimately obfuscates actionable insights and fails to address the heterogeneity inherent in treatment responses.

Sean Lee

November 7, 2025 AT 23:28When we interrogate the molecular ontogeny of rhabdomyosarcoma, the interplay between chromatin remodeling complexes and myogenic transcription factors emerges as a pivotal axis.

Michael Christian

November 10, 2025 AT 01:28Exactly! Simple language helps more people get what's going on.

Steven Elliott

November 12, 2025 AT 03:28Sure, because a dropdown menu will cure cancer.

Lawrence D. Law

November 14, 2025 AT 05:28While I respect the sentiment, it is essential to acknowledge that systematic data collection tools contribute to evidence‑based strategies that ultimately enhance patient outcomes.